White Bullies Story #1

In the past six months, I’ve been thinking of an incident that probably happened in the summer of 1979. I was about 10 years old. I am pretty sure it was my summer before sixth-grade. I simultaneously laugh out loud and am filled with embarrassment when I think of that day.

My mom dropped us four kids off at Lake Phalen in St. Paul, Minnesota where we lived—and where I am this month, visiting family. She probably went to work or ran errands. If I was ten, then my sisters were nine and seven, and our brother was six. That was normal in the 1970s and 80s. No helicopter moms for us. I remember a few white kids had moms like that. They tended to wear color-coordinated Dr. Scholl’s wooden bottom sandals with their plain and tidy outfits. They had their hair cut in bobs sometimes with a slight feathering like Princess Diana. They seemed bland, overly-attentive, and mildly oppressive to me. There was a “beach” at Lake Phalen. You know, those half-pebbles and dirt, half-sand beaches at little lakes that dot the north and middle of the so-called USA by the thousands. They usually have lots of weeds that scratch your feet and legs if you swim in them, and the fish that come out of them taste like lake down to their many tiny bones.

We definitely would have swum and my youngest brother and sister probably played in the sand. I don’t remember the details of the day until the embarrassing incident. Our mom was due to pick us up later in the day. Judging by the angles and color of daylight in my memory, the incident happened between 5 and 6 pm. Our mom would have been picking us up just before supper as we called it then.

I don’t remember how the white boy of about 12 years old approached us. I do remember that he looked like Danny Partridge from the TV show about the singing mom and siblings, The Partridge Family. For the next 45 minutes “Danny Partridge” proceeded to gaslight us. I would have said “brainwash” back then.

I recall red-headed Danny ordering all four of us like little ducklings (although I wasn’t much smaller than him) to keep walking in a line around the lake. He said his older brothers were off in the trees watching. Of course, we couldn’t see them. He told us if we didn’t keep walking where he told us to go, his brothers would come running out of the tree grove and beat us up. Lake Phalen is over three miles around and our mother was due any minute to pick us up in the parking lot.

I often laugh when I think of that day. But in that moment, we four siblings were scared. I suppose it had something to do with the fact that when we weren’t living in the country on our Dakota reservation, we lived in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul in sometimes rougher neighborhoods. In the eyes of whites, my mom was a “single mother,” but we had a lot of support from my grandmothers. When we lived off reservation in the Cities, we lived in places like the Little Earth housing project in South Minneapolis. Or we lived in a walk-up on Van Buren Avenue in Frogtown (then a working class, poor white and POC neighborhood) in St. Paul.

We lived above the Native American GED program office that my mother directed. In my childhood, children ran feral through urban neighborhoods along with the dogs, and were regularly subject to the whims of neighborhood bullies. Sometimes that involved physical beatings. I remember frequently crossing a dangerous urban street to get to third grade in order to avoid the cement walking bridge that had dark corners and mean big kids hiding, waiting to chase and beat the younger kids that came by. I was not a fast runner.

To us, this bigger white kid at Lake Phalen with the imaginary brothers was a conceivable threat. I remember feeling so sure that his bravado was an indication of actual danger. I went where he told me to go, and my younger siblings followed. In those days, I didn’t quite understand the male and sometimes white supremacist move of making oneself big and loud and assuming the rightful authority to just order people around. Do they do this in order to compensate for who knows what? A lack of real power? Maybe he was a lonely kid who got beaten on himself. Maybe he was just a mean little jerk. I mostly remember being hot, tired, hungry, and worried that our mother would have the cops out there looking for us. After walking about a mile, it was suddenly time to make a break. We were away from the trees, and we figured if his brothers were there, we might make the parking lot where my mother should be waiting (fingers crossed) before they caught us.

We ran. He didn’t come after us. No one did.

We got to the parking lot out of breath and relieved, and my mother was pissed. “Where the hell have you been!?” We told her the whole story with drama and urgency.

“What the hell’s wrong with you? There are FOUR of you. You could have taken him.” She was not sympathetic, but incredulous that we let some white kid force us to walk one-third of the way around the lake.

White Bullies Story #2

Midway through sixth grade, after Christmas of 1979, I decided I’d had enough of gritty urban life and I asked to once again move back to Granny’s house. My great-grandmother lived on our reservation in southeastern South Dakota in a small two-bedroom house with very few doors, and many books. There were no neighborhood bullies, just the neighborhood dogs who never knew a leash and who would chase extra hard when I rode my bike on small-town streets, my legs on the handlebars to avoid getting bit.

I lived with Granny for the next several years. As luck would have it, I found my white bullies on the junior high playground of the reservation border town. They were three middle-class white girls and all three were cheerleaders. That part cracks me up. It sounds like a 1980s teenager film. Jeanie, Jackie, and Shelby (names changed to protect the not-so-innocent) harassed me daily on the playground after lunch. One spring afternoon when there were still patches of dirty snow on the ground and the prairie wind was blowing as it often does, I was standing off alone for some reason. I did have a core group of friends, but I was apart from them. The three cheerleaders decided to pounce, not physically, but emotionally. They saw me alone and recruited a go-between to give me their message of hate, as if I didn’t already know it. They sent Tina, a girl in their grade, which was one above mine. I don’t remember the details of their message. But I saw red, as they say. Not because of whatever they said, but because they sent Tina. She was a short rocker-looking girl who also looked white, but she hung out with Natives mostly. She could sprint like a rabbit. I never knew if she was Native or white. But I had considered her, if not a friend, then a friendly. I liked her contradictions. And I knew she only came bearing the cheerleaders’ scornful words because she was intimidated by them. That was the final straw for me.

My usual tactic with their mocking was to stoically ignore them. I would summon all of my courage to walk silently past them, refuse to look at them as they huddled in a little group and laughed at me in the hallways or in the lunchroom. Man, my days were stressful. In retrospect, I understand that their derision of me might have been in part due to their confusion and perhaps even jealousy. Or maybe they were just mean girls. I was in many ways a small-town, timid Native kid who often kept quiet so as not to attract negative attention. I lived with my great-grandmother and great-aunt in a humble little house. We didn’t have a car. Granny never learned to drive. But because I occasionally lived in the more urbane Twin Cities and because my great-grandmother who didn’t have a lot of money would still spoil me and order some of my clothes from a higher-end catalog - I was the first person in my school to have the original Gloria Vanderbilt signature jeans. I don’t know if people who weren’t adolescents in 1980 can fully grasp what a fashion coup that was. The small-town kids in Wranglers and Lee jeans thought I dressed weird, or so I heard. I think mostly it was hard to assign me to some junior high social category box in our red/white racially divided town.

Let’s return to Tina. Mean girls coming after me was one thing, but them intimidating an otherwise kind girl into doing their dirty work seemed even more unethical. I just looked at Tina, then I turned toward the cheerleaders. I walked up to Jeanie, Jackie, and Shelby and let them have it verbally. My mouth, it turns out, is faster than my legs and tougher than my fists. I don’t remember exactly what I said. I do remember swearing at them and using the F-word for probably the first time in my life. I told them what I thought of them. Then I turned away and put one foot in front of the other with forced calm. I walked straight up the front steps into the old brick school building. I can still feel the prickles in my back when I think of it. My backside was waiting for the attack of the cheerleaders, for their collective weight on me. I walked and I waited for them to maul me, pull my hair and drag me to the ground. But I didn’t care. I’d had enough. I walked up the steps. I opened the heavy school doors, still no attack. I arrived in the school foyer and turned around to look back outside through the windows in the great doors. The cheerleaders were standing where I left them, their mouths hanging open. “Are you kidding me?” I thought. “That’s all I had to do?” I was so pissed at myself for being silent through a year of their relentless mocking. I had done it again, acted like that day at Lake Phalen.

Unlike with Danny Partridge, I didn’t fully believe what the cheerleaders told me. Yet I still struggled to wholly reject their words and judgement. I was in an internal battle when they daily assaulted my self-esteem. On one hand, I did not believe that we as Dakota people were culturally beneath whites as they would explicitly or implicitly tell us we were. I knew too much history. My family and our tribe made sure of that. I’d also been taught indirectly that I was an individual self within a broader Dakota people, and that was a worthy position to be in. I linked in my mind what I individually experienced as a seventh-grade Native girl in rural South Dakota to what happened to Dakota, Lakota, and other Native people in what became the states of South Dakota and Minnesota in 1862, 1887, 1890, and 1948. I knew my injuries were comparatively small next to those of my ancestors, yet my experience was in part shaped by that history. I also grew up in an era of American Indian Movement (AIM) activism in a part of the country that was at its epicenter. I got young a sense of the workings of structural and anti-Indigenous racism that enabled not only the theft of land, but ongoing settler cultural attempts to attack us as Peoples and as individuals. I was trying in my inexperienced child’s way to embody what my elders, who I trusted intellectually, told me to be true.

Back in 1980 at the age of 12, I did not, of course, have these complicated words to describe a structural versus individual analysis. But I remember clearly how I felt; I can describe it now. I trusted our People’s interpretation of our own history, yet I also felt unsure of myself individually. I still listened too much to the cacophony of white voices. It was hard to not believe at some level the words of white children who were born of the dominant power structure in my hometown and who had already learned themselves, and continued settler-colonial brainwashing.

But after that spring day in seventh grade, everything changed for me. I had publicly and assertively challenged the bullying. Simultaneously, I challenged the idea that challenging their power was too risky, that they were too formidable. After that, I was still afraid, but less so. I got even mouthier the next year in eighth grade. I was in the principal’s office almost daily for pushing back against the mocking with my own disparaging critique. Our soft-spoken and nerdy principal, it turns out, was my ally while the bullies among my classmates and some of my teachers were not. I would like to think I spoke “truth to power” as they say these days. In junior high, it seemed like those middle-class white kids and the teachers who permitted their bullying had a lot of power.

Every day over the past seven months, I’ve recalled Danny Partridge and the cheerleaders after years of not thinking about them. I thank them for hard lessons. It turns out, they prepared me for the current onslaught of gaslighters, and the institutional decision-makers who permit them.

White Bullies Story #3

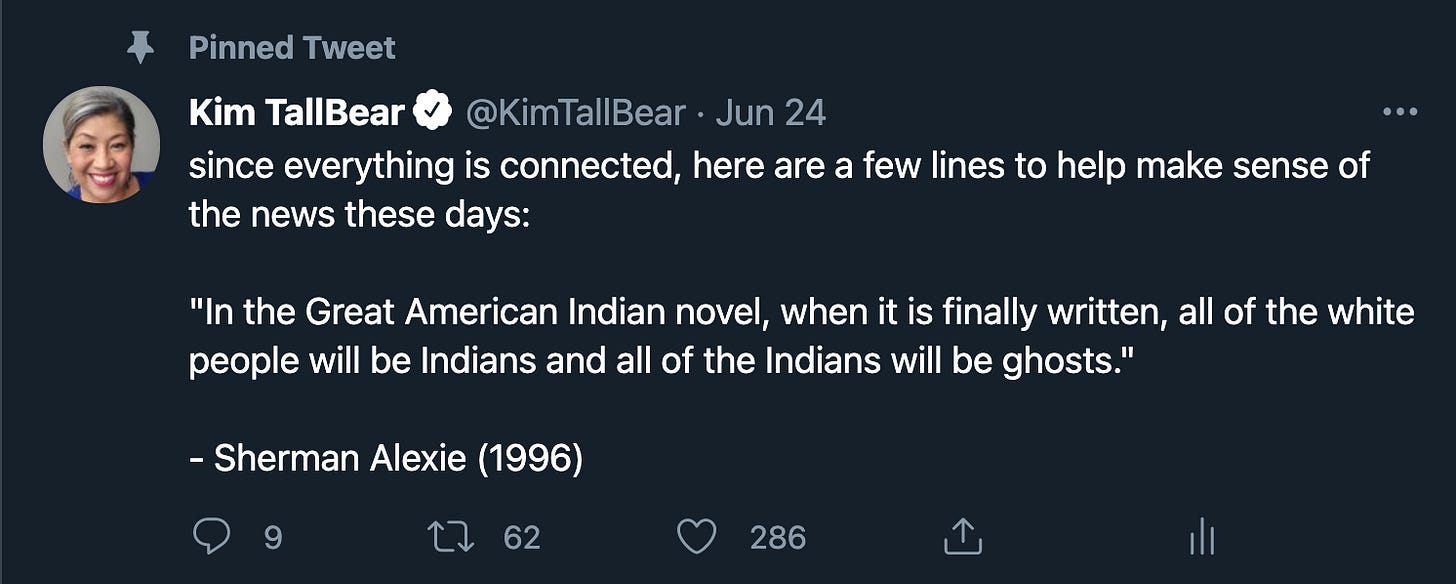

My readers will know about the so-called Pretendians—those who falsely claim or exaggerate Native “identity” via false or often tenuous claims to Indigenous ancestry and affiliation. I’ve written, tweeted @KimTallBear, and podcasted extensively on this problem during the last seven months. Several major stories have broken about well-known people—a film director, a high-profile academic, and an artist—who for years claimed Indigenous identity, thus garnering lucrative employment and funding opportunities as well as social capital they might not otherwise have had. All three are now known to have fabricated their ancestry or wildly exaggerated their Indigenous affiliations.

Another recent breaking story involves an anonymous report challenging the Indigenous identities of six people affiliated with Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. “Investigation into false claims to Indigenous identity at Queen’s University,” was published as a Google doc on June 7, 2021. The author(s) write in the introduction that “The report includes an analysis of six people currently associated with Queen’s University who, after extensive research, appear to be falsely claiming Indigenous identities (primarily “Algonquin”). It also raises significant doubts about the Ardoch Algonquin First Nation’s (AAFN) claims to represent an Indigenous membership.”

Queen’s University issued a statement a few days later that rejected the charges, and with it the widespread severity of this problem. But the heated debate about the Queen’s situation continued. On June 27, University World News published an article, “High stakes in Queen’s faculty Indigenous Status row,” that is among the most comprehensive takes I’ve seen in a non-Indigenous publication of the material implications of this widespread form of Indigenous appropriation. In another article published June 28 in Queen’s Gazette, soon-to-be Queen’s University Chancellor and high-profile Indigenous figure in Canada, Senator Murray Sinclair, was quoted: “It is clear that self-identification of Indigeneity no longer works…We must go beyond an honour system and include voices from Indigenous communities across Turtle Island.” We don’t know how hard Queen’s will ultimately tackle this problem, but they were clearly forced to do more than double-down on their initial denial that fraudulent claims to Indigenous affiliation are a problem.

Figuring out how to institute guidelines for Indigenous affiliation claims in faculty, staff, and student hiring and admissions that go beyond Indigenous self-identification is not easy. Especially when universities across Canada and the US are mostly run by white people who are unqualified to determine who is Indigenous in the course of hiring, student admissions, and funding. To date, universities have largely shown themselves to be unwilling and/or incapable of tackling this problem. In fact, many are culpable in growing the problem in the last forty years by uncritically forwarding “multiculturalism” discourse at the expense of more aggressive and materially-focused “affirmative action” policies. I wrote more about that problem in my June 14 Unsettle essay linked to in the notes below. I and others have explained that individuals and groups appropriating Indigenous “identity” (not a term I prefer, but one commonly used) is a final act of colonial appropriation.

I tweeted on June 22 a thread that I will recap here. I noted that “I don’t feel like most people who play Indian are being deliberately disingenuous.” But that does not mean that I give them a pass for their fabricated histories and lies. I have come to believe, by observing this phenomenon closely for years, and studying it in relation to DNA testing, that many false claimants of Indigenous identity suffer from a nationalist colonial delusion that they have as settler-state citizens unquestionable moral and sometimes legal rights to occupy Indigenous representations and identities just as their nation states claim moral and legal right to occupy stolen Indigenous land. How many US and Canadian citizens actually question their nation-states’ legal rights to occupy these stolen lands? Challenging their claims to BE us, to occupy our identities is similarly daunting.

Like with adolescent bullies on a white-dominated playground, it has seemed too risky to publicly confront race shifters and their accompanying resource appropriation. This is true despite decades-long whisper networks across Indigenous territories about such cases. Like the bullies of my childhood, I am sure the corruption on the societal play(ing Indian)ground is committed by people who truly believe they are morally justified when they harangue and patronize us into accepting the authority of their distant, individualistic (rather than collective and relational) ancestral descent narratives of “identity.” In such accounts, especially in the last several years of heightened (social)media attention to such cases, I’ve observed three narrative patterns that white-dominated cultural and governance institutions also help script and stage (also see TallBear 2013 and TallBear 2021).

1) It’s all too complex and fluid: Paradoxically, while the playground bullies fetishize a long-ago or fabricated ancestor (i.e. a “one-drop rule”), they accuse us of “oversimplifying identity.” Indigeneity and within that tribal- or people-specific “identities” are supposedly just too “complex” for us to say anything definitive about them. Everything is “fluid.”

2) Distant ancestry claims are the same as our stolen relatives’ claims: We are told when we question their generations-ago claims that we are simultaneously rejecting the repatriation of our close kin (i.e. the scooped and stolen generations), as if these two sets of distinct situations are the same. Indigenous people who push back are shouted down as nothing more than blood quantum savages who are too colonized to ascertain who we should claim. The scooped and stolen face formidable challenges, but they have the capacity to connect or reconnect when they have living kin and nation to remember and claim them. Non-Indigenous people underestimate Indigenous community collective memory and literal, physical archives.

3) Indigenous communities are the perps while those who’ve lived as (usually) white are our victims: They encourage the idea that they are victims as much or more than those of us who don’t have to research an ancestor generations ago, but who actually come from living Indigenous families and communities. We are treated as if we Indigenous people and nations who have never not lived as Indigenous and who have lost almost all of the land and governing authority actually hold the power; instead those who for generations “hid” in whiteness are our supposed victims.

They relentlessly attack our focus on lived relations and substitute the dead ancestor figure (sometimes named, sometimes not) as the grounds for their Indigenous claims. They undermine our confidence. They cause us to question our own judgements, definitions, and understandings of our social realities. Some of them gain considerable material and social benefit while putting Indigenous people individually and structurally at financial, social, and emotional risk. They are, in effect, “gaslighting” us (Tobias and Joseph 2020).

Like my challenges to the cheerleaders and to Danny Partridge, this race shifter phenomenon has seemed for decades too formidable, too risky to openly and loudly challenge. But as I learned at the age of twelve, everything can change in one day, or perhaps in one year. We see case after case now breaking with Indigenous identity appropriators being researched and named by academics, report writers, investigative journalists and in well-researched social media in the US, Canada, and Australia.

Privileging Indigenous collectivity (both kinship and “nation”) and thus reclaiming close kin kidnapped and alienated from us by settler institutions that include residential schools, foster care, and Indian Act rules is quite different than allowing unfettered access to our collectives by people who come from generations who have lived as not Indigenous, most often with white privilege. If we adhere to social constructionist ideas more than biologically essentialist ideas, it seems safe to say that those who claim a long-ago Indigenous ancestor among tens, hundreds, or thousands of ancestors are actually constituted as other than Indigenous to these lands. Their narratives of “inclusion” are actually assertions of entitlement to Indigenous resources, which is yet more colonization.

But the time of reckoning with this final act of Indigenous appropriation might just have arrived. I keep hearing my mother’s voice in my head: “What the hell’s wrong with you? You can take them.”

Additional Background Reading and Listening (in addition to links in text)

Media Indigena podcast. “Contemplating the Consequences of Colonial Cosplay” (Pt. 1), Episode 245, February 24, 2021.

Media Indigena podcast. “Creating Culpability for Colonial Cosplay" (Pt.2), Episode 246, February 27, 2021.

Kim TallBear. “We are not your dead ancestors: Playing Indian and white possession.” Unsettle. June 14, 2021. Both text and audio here.

Kim TallBear. “Playing Indian Constitutes a Structural Form of Colonial Theft, and it Must be Tackled.” Unsettle. May 10, 2021. Audio here.

Heston Tobias and Ameil Joseph. “Sustaining Systemic Racism Through Psychological Gaslighting: Denials of Racial Profiling and Justifications of Carding by Police Utilizing Local News Media.” Race and Justice 10(4) (2020): 424-455.