Playing Indian Constitutes a Structural Form of Colonial Theft, and It Must be Tackled

Indigenous peoples’ erasure in the dominant U.S. racial imaginary exists alongside our actual survival as peoples that refuse to be fully absorbed into the political and physical bodies of others. This compels a phenomenon that Harvard University historian Philip J. Deloria calls “playing Indian.” In his 1998 book by the same name, Deloria focused on mascots, boy scout rituals, and other forms of dressing up as Indian. He did not focus on the false claims to Indigenous ancestry or “identity” that I will focus on here. But his historical investigation also supports an analysis of the centuries-long, intractable practice in US American life of a more literal form of playing Indian: false claims to Indigenous ancestry and identity in which often multi-generational players can forget they are pretending.

From a rich archive of historical data, Deloria draws on British writer D.H. Lawrence’s analysis of an “essentially ‘unfinished’ and incomplete” U.S. American consciousness that produced “an unparalleled national identity crisis.” Lawrence saw the Indian as “at the heart of American ambivalence…Savage Indians served Americans as oppositional figures against whom one might imagine a civilized national Self. Coded as freedom, however, wild Indianness proved equally attractive, setting up a…dialectic of simultaneous desire and repulsion.” (Deloria 1998, 3). Lawrence wrote that “No place exerts its full influence upon a newcomer until the old inhabitant is dead or absorbed.” Therefore, the “unexpressed spirit of America” could not be fulfilled without Indians either being exterminated or assimilated into white America (Deloria, 4).Deloria summarizes:

The indeterminacy of American identities stems, in part, from the nation’s inability to deal with Indian people. Americans wanted to feel natural affinity with the continent, and it was Indians who could teach them such aboriginal closeness. Yet, in order to control the landscape they had to destroy the original inhabitants…half-articulated Indianness continually lurk[s] behind various efforts at American self-imagination (Deloria, 5)

I write elsewhere that “identity” is a poor substitute for relations, that it “does not necessarily imply ongoing relating. It might imply discrete biological conjoinings within one’s genetic ancestry and it can spur alliances, but it can also exist as a largely individualistic idea, as something considered to be held once and for all, unchanging within one’s own body – whether through biological or social imprinting – as one’s body’s property” (TallBear in Hokowhitu et al, 2021: 474). Fabricating relations that did not exist are the crux of the problem with false or overreaching “identity” claims.

I have given multiple talks at universities across the US, Canada, and globally; offered commentary on various aspects of the phenomenon of playing Indian in multiple podcasts and Twitter threads. Some of you will know my analyses related to DNA testing and Indigenous ancestry claims, especially related to Elizabeth Warren’s stereotypical Cherokee ancestry claims that first came into the public eye in 2012, and her regrettable DNA test back in 2018 (Bahrampour 2018, BBC 2018, Chen 2018, Friedler 2019, Johnson 2018, Kessler 2018, KUOW 2018, McFarlane 2018, Miller 2018, Raff 2018, Schilling 2018, Smith 2018, Uyehara 2018, and WYNC Studios 2018). I’ve also been called to weigh in on other high profile Indigenous “identity” fraud cases, including Canadian writer Joseph Boyden and U.S. based academic Andrea Smith (CBC 2017 and Barker et al 2015). I’ve also been asked to comment publicly on many more, including more recently that of Canadian director, Michelle Latimer, who also asserted Indigenous identity and has been publicly challenged for a lack of evidence (Deer and Barrera 2020).

Warren, Boyden, Smith, and Latimer are only four among many who make such claims. A current investigation by independent Diné and Dakota journalist, Jacqueline Keeler, demonstrates the widespread occurrence of false identity claims by public figures in academia, the arts, literature, TV/film, and other fields. She and her research team have compiled a much debated “Alleged Pretendians” list of nearly 200 individuals, and she plans to calculate the financial return to them in their roles as public-facing Natives. You can go to her Twitter feed @jfkeeler for more information on the list. I’m not doing a fuller explanation and analysis of the list here, but rather touching on structural problems related to “pretendianism” and how those are reflected in debates surrounding the list.

I have been working on a book chapter for a while now on the predicament of playing Indian in a contemporary mascot and identity claims context. However, given the recent vociferous social media targeting of Keeler and her list, I decided to write this shorter piece and quickly. I have already discussed the list at length on air with fellow Media Indigena podcasters, Rick Harp and Candis Callison. You can listen to our two-episode discussion, “Contemplating the Consequences of Colonial Cosplay”, Part one:

and “Creating Culpability for Colonial Cosplay” part two:

We dive deeply into the issues in the Media Indigena episodes and I figured that was sufficient commentary from me on this issue.

However, I woke up yesterday morning to a message of concern from one Indigenous person from here in Canada about the social media targeting of the list and Jacqueline Keeler. The messenger is a person whose politics in defense of Indigenous peoples and lands I deeply respect. They are also a global and anti-imperialist thinker. They asked me, had I seen the drama and what was being done to Keeler on Twitter. I responded that yes, I have, and I’ve also occasionally been tagged in the past few days by Twitter users pressuring me and others to “unfriend” Jacqueline Keeler and disavow our professional associations with her. But I ignore Twitter strangers pressuring me, especially strangers with subpar analyses based on shallow examinations of evidence and deflection. I write and speak complex and nuanced analyses every day on these issues. “Identity” and relations in broad strokes are central to all of my work. Engaging in conversations that are essentially a cacophony of echoes across centuries of colonialism is complex, exhausting, and often thankless. I choose where and how I allot my time, and so do others who stand in different places.

As a journalist and commentator respectively, Jacqueline Keeler and I have communicated multiple times since the Warren incident in 2018 about the identity fraud problem. As I stated on the Media Indigena episodes, Keeler and I were part of a group of commentators, genealogists, and reporters who weighed in on the Elizabeth Warren situation in 2018 and all the way back to 2012. In 2018, when the story really blew up because of Warren’s expected presidential run and her misguided DNA test, some of us began to communicate as a group in order to manage our responses to the issue and to make sure Cherokee voices were foregrounded where appropriate. Back to my messenger yesterday morning: they asked me, given my larger platform, to please weigh in on the attempted de-platforming in their words of an Indigenous woman, Keeler, on Twitter by other Indigenous people.

Then yesterday afternoon, I also talked for a couple of hours with two Indigenous women from back home in South Dakota about the list and the social media targeting of Keeler. These two women offered me advice from rural tribal communities in South Dakota about what people are thinking of this situation, some of the concerns tribal people have, and what my friends think I should emphasize in writing this. They too agreed that I should weigh in because of my platform and my background in studying this issue. They both thought that not everyone who is similarly concerned with the grave and widespread problem of fraudulent identity claims is in a position to weigh in. Others besides myself feel more at risk or vulnerable by publicly speaking on this topic, and they don’t have the audience that I have even if they did feel okay to speak. This sentiment of fear of the personal and professional risks of Indigenous people speaking out is also expressed by Inuit documentary filmmaker and activist, Alethea Arnaquq-Baril in the February 15, 2021 Canadaland podcast on Canadian filmmaker Michelle Latimer’s Indigenous identity case. The Canadaland podcast is an exemplary treatment of this issue and the considerable pain and discomfort it causes in Indigenous communities when those who should be in good relation with our communities betray us through false identity claims. And paradoxically, sometimes those with unsupportable ancestral claims actually do come into lived relation with our communities, but that does not negate the harm done by their contributions to this overwhelming structural problem.

I won’t do an exhaustive assessment of all of the charges against Jacqueline Keeler circulating on Twitter. I will focus on a few charges that I think are at the center of the firestorm, some of which I think are badly analyzed and under-evidenced, and that regularly inhibit us undertaking the necessary analyses to seriously undercut the phenomenon of false ancestry/identity claims.

1) A central charge is that the list is anti-Black. I have yet to see this backed up by evidence. As I understand it (I last saw the list a few weeks ago), there is one Black person on it. And about 180 white people. The rest are people that are probably best identified as “Latino/x” or “Asian.” People look to be not actually analyzing the list itself but deflecting toward other threads and conversations, some years old, in their charges that Jacqueline Keeler (and therefore the list with one Black person?) is anti-Black.

2) There are a couple of individuals on the list known by other researchers too to have no Native ancestry, but with tribal citizenship. They are both white coded individuals; I say that mainly in light of the charges of anti-Blackness. There are some especially strong objections in Indian Country to these two individuals being on the list. My understanding, knowing their media documented stories, is that they are on the list because their histories involve fabricated ancestry. Nonetheless, those two are claimed today via tribal citizenship for complicated, but legitimate reasons. Some in Indian Country feel that if the two tribes involved confer citizenship on those individuals, end of story. They’re not “pretendians.” I see their point. I also see the point of highlighting the shared history of fabricated ancestry in their stories. Keeler is attempting to show how widespread and longstanding is the practice of fabricating Indigenous ancestry in order to claim resources, be it land in the 19th century or scholarships, university admissions, grants, prizes, and job opportunities in the 20th and 21st centuries.

3) Perhaps the most frequent charge against the list is that it is a list, and feels McCarthyesque to people. I don’t find this charge compelling. I am interested in hearing substantive and nuanced arguments that a list is inherently problematic. I just haven’t heard them yet. The McCarthy cliché isn’t sufficient for me. No one is advocating rounding up false identity claimants, interrogating, imprisoning, or deporting them. No one is disallowing their speech. In fact, they are being asked to speak and to account in a way that makes their relations right. We have all kinds of lists in this world that designate who is eligible for all kinds of resources. This is a list that does the opposite. It says, no, actually these people receiving resources as public Natives are not in fact Native at all. In fact, most of them are white people with well-documented white and European ancestries, and should therefore not be accessing benefits as Native people. We debate lists regularly in Indian Country, chief among them enrollment lists. I’ve also written and spoken extensively about the dynamic process of tribal citizenship and enrollment and the difficult job that Indigenous communities have in deploying "citizenship” in a colonial infrastructure in which we must survive, but which was forced onto us as the only alternative to death.

4) Another charge against the list, although this seems to be less common on social media than the previous three points, is that it should not have been made available to anyone outside of Keeler and her research team until it was fully vetted, and Keeler’s associated story published. This is a question I have myself. I am not a journalist. I don’t understand why give members of the public access via a Google doc to a list that is not completely vetted, and the publication of this investigation not yet written. I will be interested to see a fuller journalistic methodology published explaining this choice. One of my South Dakota acquaintances also expressed this interest and concern.

Let me return to the rest of the points that my two acquaintances in South Dakota emphasized when we talked yesterday, the points they thought I should emphasize here. Remember that Jacqueline Keeler has Dakota relatives in South Dakota, while she is a citizen of the other People she comes from, the Navajo Nation. She is not a total stranger to the two women I talked to. We always know someone who knows someone’s family. Like many of us, they are not comfortable with her method. And one of the women expressed the concern of some people in her own tribal community that issues such as “identity fraud” among public figures might not be the most pressing issue for our communities. My friend asked me why I thought this was a pressing issue that will actually harm many Indigenous community members. I explained to her the structural trickle-down of having non-Indigenous people with non-Indigenous community standpoints rising through the ranks to represent us and theorize Indigenous peoplehood, sovereignty, and (anti-)colonialism. These people become “thought leaders,” institutional decision-makers, and policy advisors to governmental leaders with regulatory and economic power over our peoples. They then shape academic and public discourse about who we allegedly are, what our lives allegedly look like, and what they think should be done about and to us. My friend said, thank you for clarifying, and she agreed it is an important issue.

She also told me one of the reasons that more traditional people don’t call out publicly those who falsely claim Indigenous ancestry is that it is not the way things are often historically done. When someone is acting inappropriately, they “will be given enough rope to hang themselves.” One does not always come at someone making false claims directly, but over time, the inappropriate person shows themself to be who they truly are. They will eventually out themselves. Perhaps this has happened in various cases, but more privately.

This leads to another point my friends in South Dakota made. They agree with something Jacqueline Keeler has pointed out: that while the pretendian phenomenon is widespread and has been going on for centuries, we often do not share these stories widely—perhaps this is related in our Oceti Sakowin case in South Dakota—to not directly confronting this problem so often. We also may feel pained and guilty and disbelieve ourselves before finally facing overwhelming evidence that something isn’t right. This is especially the case when pretendians today and historically marry into our kinship structures. One of my friends from home said that we will do much to protect our children and that includes tolerating the lies of individuals who have born children with our people. Jacqueline Keeler has also called attention to the strategy of marrying in. And I’ve read the work of Cherokee genealogists who also cite that as a not uncommon strategy historically for people to get their hands on Native land and resources. As Alethea Arnaquq-Baril said on the Canadaland podcast, it is painful to finally confront someone we know and care about once we realize there are many holes in their story. We don’t tend to go public with these stories until we feel we have no choice. In the Andrea Smith case, the confrontation took years and was deeply painful for those who were closest to her. They were the ones who did the confronting. They took risks and paid a price in terms of loss of relationships and professional opportunities. These risks are what people in the Canadaland episode feared, and they noted that many people refused to speak on air precisely because of those risks.

Because of these legitimate and careful ways in community of addressing the problem of false ancestry claims, our many distinct accounts of false assertions remain siloed and therefore the deep structural problem is obscured. Instead, we make jokes about wannabees and Cherokee great-grandmother princesses. We often laugh privately and publicly at the phenomenon without calling out individuals. Maybe in our ongoing laughter, we are sending a message to the “pretendians” within ear shot: “We know. What are you going to do about it?” When pointed cross-Native conversations about this issue do occur, it tends to be in whisper networks given the preference expressed by many who’ve weighed in on this debate for specific communities calling their own in or out, and from my friend’s perspective, for people learning their lessons in due time. This more delicate isolated approach to confronting pretendianism can obscure its structural impact. The list is an uncomfortable and controversial attempt to make the impact clear.

At the end of our conversation, my friends told me, speaking of the Twitter storm and targeting of her character, that one does not have to like Jacqueline Keeler to agree that false claims to Indigenous ancestry are a serious and growing problem and that something must be done.

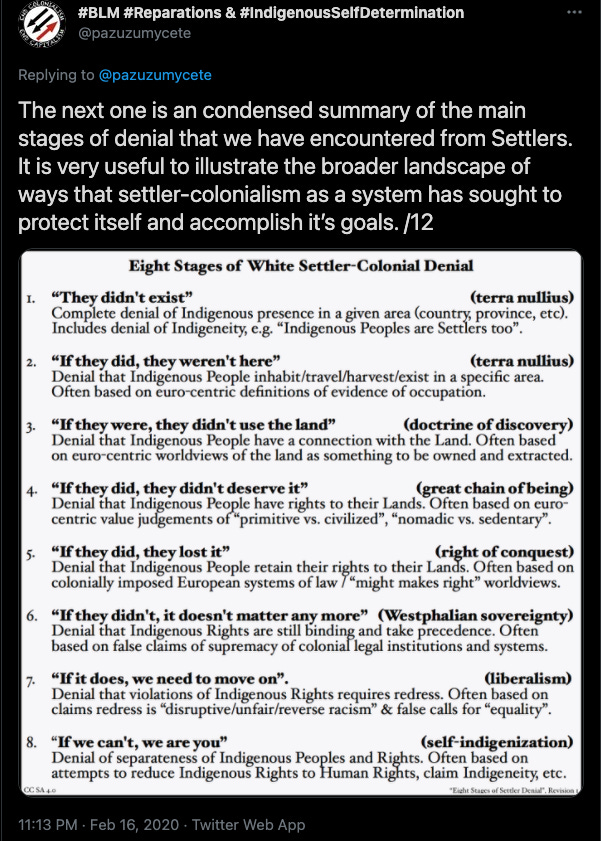

While I don’t yet see how this list is anti-Black or McCarthyesque, I clearly see that false ancestry and identity claims are a final act of theft in a long history of multiple layers and strategies of theft. See the pithy schema below to understand this point more fully.

Notice the above tweet has a #BLM hashtag in it along with #Reparations and #IndigenousSelfDetermination. These hashtags that represent a growing number of anti-imperialist, anti-colonial Black, Indigenous, and other POC thinkers in global conversation indicate that racialized groups can support each other’s entangled struggles. These are the moves that excite me. These are the thinkers I am most edified by. But this does not mean that I will ignore the fact that we can all be complicit in different ways in one another’s exclusion from power and resources. So let me return again to a chief charge against the list, that it is anti-Black despite the vast majority of people on the list being white. Can non-Indigenous Black people and POC (to use US-based lingo, that is, “People of Color”) be complicit in pretendianism and anti-Indigeneity broadly?

Yes.

In my experience living, working, and/or traveling in 49 of 50 US states plus most of the provinces in Canada (I’ve not yet been to the territories), false claims to Indigenous ancestry/identity happen across racial groups. That said, the foundation of playing Indian and Indigenous appropriations is white supremacy. I’ve written elsewhere about how US racial formations attempt to eliminate Natives from the land in part by whitening us (Reardon and TallBear 2012). This whitening of the Indian works in service of the above stage eight of white settler denial and appropriation.

One can understand that the foundation of all of this is white supremacy and ultimately the settler state’s appropriation of EVERYTHING Indigenous. And it is still then possible to point out a Black person’s false Indigenous identity claim (or their anti-Indigenous mascotting and disparate treatment of Native people, e.g. TallBear v. Moniz 2018). This is not in and of itself anti-Black. Just like pointing out a non-Black Indigenous person’s anti-Blackness is not in and of itself anti-Indigenous.

Why is the list mostly whites? Because white people (and, by the way, also actual Natives who code as white) have more access to socialization afforded by white privilege that puts them disproportionately into positions of influence. Whites and those who are white-adjacent can rise through institutional ranks more easily because they’re visually and then potentially more socially simpatico with that structure. The Canadaland podcast also noted this situation, wherein those individuals who are culturally intelligible and socially comfortable for whites or even attractive by normative white standards garner outsized attention and opportunity. This is a reason that pretendians take up such disproportionate Indigenous space. In addition, white people’s racial definitions not only permit white Natives, they actively seek to whiten the “Indian” as I already pointed out.

Jacqueline Keeler has stated that she’s not interested in investigating your uncle at the family barbeque with a Cherokee great-grandma story. She’s investigating those who make often lucrative livings claiming Indigeneity, and who are more public facing. And she’s going to calculate their appropriation of resources from Indigenous people/communities who would otherwise benefit from access to the university admissions, grants, employment, and other opportunities garnered by false claimants.

Calculating the amount of fat a pretendian takes from Indigenous people is a critical structural analysis. (For those of you not in the know, the Dakota word “wasicu” for white person allegedly means “they who take the fat.” That is the dominant translation, although my Dakota language instructor told me another less critical translation.) Such analyses are never comfortable, not for those implicated in the taking nor for their friends and colleagues. Sometimes too their families are pained and uncomfortable. What has been and continues to be taken? Indigenous lands and relations with nonhuman relatives; our governance structures; our children; resources beneath the land; our bones, blood, and DNA; and finally, our rights to define ourselves and say who belongs to us and who IS us. This in turn, leads to the appropriation of monies and resources allocated to/for Indigenous peoples, often through multi-generational, arduous struggle by Natives in community to advocate for their people who are disadvantaged by colonialism. False claimants to Indigenous identity are essentially doing what 19th century traders did who stole annuities as middle-men between the federal government and tribes. They are doing what squatters on Indigenous lands did. Like pretendians, traders and squatters sometimes married Native people. Some of them claimed to be Native themselves and centuries later, their descendants continue to live the lies. Perhaps the family memory of that lie has been lost or is so distant in the genealogy that it is but a whisper. It is easy to ignore. Or surely one’s parents or grandparents or great-grandparents did not lie. Surely no one lied, not for land or money or opportunity.

It is not only many more individuals than we wanted to admit, but the US nation state itself that operates out of historical amnesia and whitewashing of events that do not fit within a benevolent telling of US foundations and the mythology of the pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps American dream. Central to that dream of a clean national slate is not only the enslavement of Africans, but also very much the erasure of Indigenous peoples. Again, see the Eight Stages of White Settler-Colonial Denial. No one has been immune from Indigenous erasure. It saturates every single one of our institutions.

Keeler’s and her team’s list indicates that the overwhelming number of the false claimants who benefit financially from pretendianism are whites. The white power structure always makes sure it benefits most. The stories behind some Black people’s history of false claims to Indigeneity are painful in a way that I find heart-wrenching, but that does not mean they can also not be appropriative. Such claims are related to both forms of white supremacy I’ve mentioned: 1) Indigenous-erasure, which includes whitening the Indian; and 2) anti-Blackness that emerges from the Black/white binary and which has compelled some Black people historically to reach for the romanticized Native in their history as a small bit of relief from violent anti-Blackness (The National Archives Experience 2009).

Finally, I want to reiterate something I said on the Media Indigena Colonial Cosplay episodes: I’m seeing the disconnected conflate their situation with frauds. A person scooped from their Indigenous family as a child, or the child of a Native person who moved away from community or does not meet blood-quantum criteria is not the same as a person fabricating an identity out of two Indian needles deep in the 19th, 18th, or 17th centuries of their ancestral haystack. The latter have no capacity to connect to a living community if their relations have all been non-Indigenous, usually white, for centuries. The former can (re)connect. It is dismaying to see the (re)connecting throw their lot in with and defend total fabricators of Indigenous ancestry. That move, at least on Twitter, seems to involve emphasizing individual wounds and challenges over the needs of the very Indigenous collectives people say they want to (re)connect with.

I am eager for the more substantive analysis of this issue that will come from our communities when this social media firestorm around the list has quieted. I will continue to try and filter out the ad hominem attacks on Twitter (I deleted Facebook several months ago), deflection, and bad-faith analyses of critical structural critiques of largely white appropriation of Indigenous resources. One of my South Dakota friends lamented, as have others across the US and Canada, how much time Indigenous people spend dealing with situations like this instead of working on all of the projects and relation-building that we would rather prioritize. We are always having to push back, assert our claims and authorities, and be in a defensive position. I have been writing all night and the sun is now fully up.

When will the appropriations cease? How will restitution of stolen resources be made? Those who knowingly played Indian or who find they’ve been living within multi-generational mythologies of Native ancestry must reckon with their complicity in trying to absorb the Native into “America.” I have no idea how such people can possibly make material restitution for what they have taken. But I do know that they should be capable of confronting that question and the truths and lies of their histories. Indigenous Peoples need individuals to make examples of themselves, face hard truths, not deflect or double-down when confronted with evidence.

My friend ended our conversation yesterday with an assessment that while many in our communities might traditionally wait, hold back, and see what happens with a person who violates our social norms, some in our communities do take these things head on. But that’s not everyone’s role. For the fewer who do attack a problem directly, they put themselves at greater risk. But again, we each have our role and I do not diminish the persons who for reasons they may keep to themselves stay quiet.

I reiterate that I have questions about the strategy of the list as do my friends back home. We hashed over methodological and ethical questions on Media Indigena. I still haven’t answered those questions. But I do know that the discomforting project of the list is a reflection of the great and perverse risk to Indigenous communities for hundreds of years now by settler appropriation of everything. I’ve also been asked in the last couple months since the list came into public view to be on several advisory and discussion panels taking more assertive approaches to regulating access to institutional resources reserved for Indigenous people. I suspect Jacqueline Keeler has helped wedge open a very heavy door; I see others walking quietly through that door to confront this issue more directly than we have been able to confront it. I will not walk through that door and not acknowledge the risks she is taking by refusing to be the stoic, noble Indian.

Sources

Tara Bahrampour. “Elizabeth Warren’s Refusal to Take a DNA Test to Prove Native American Ancestry was Probably a Smart Move.” The Washington Post. March 14, 2018.

Joanne Barker et. al. “Open Letter from Indigenous Women Scholars Regarding Discussions of Andrea Smith,” Indian Country Today, July 7, 2015 (September 12, 2018).

BBC. “US Senator Elizabeth Warren Faces Backlash After Indigenous DNA Claim.” October 16, 2018.

Canadaland. The Convenient ‘Pretendian,’ Ep. 359. February 15, 2021, .

CBC. The Current. With Anna Maria Tremonti. “Indigenous Identity and the Case of Joseph Boyden.” January 5, 2017. .

Angela Chen.“No matter what Elizabeth Warren’s DNA test shows, there’s no genetic test to prove you’re Native American.” The Verge. October 15, 2018.

Ka’nhehsí:io Deer and Jorge Barrera. “Award-winning filmmaker Michelle Latimer’s Indigenous identity under scrutiny,” CBC Indigenous. December 17, 2020.

Philip J. Deloria. Playing Indian. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998.

Delilah Friedler. “Natives are Split Over Rep. Deb Haaland’s Endorsement of Elizabeth Warren.” Mother Jones. August 1, 2019.

Rhiannon Johnson. “Canada Research Chair Critical of U.S. Senator’s DNA Claim to Indigenous Identity.” CBC Indigenous. October 15, 2018. .

Glenn Kessler. “Just About Everything You’ve Read On the Warren DNA Test is Wrong.” Washington Post. October 18, 2018.

KUOW. “Senator Warren Takes the DNA Test.” By Bill Radke. Interview with Kim TallBear and Rick Smith. October 15, 2018.

Matt Miller. “A DNA test won't explain Elizabeth Warren's Ancestry.” Slate.com., June 29, 2016.

The National Archives Experience. American Conversation: Henry Louis Gates Jr. February 5, 2009.

Native America Calling. “Monday, February 2017 - Native Americans and Civil Rights.” Interview with Thomas Birdbear and Jody TallBear [listen at 37:45 and 52:15].

Jennifer Raff. “What Do Elizabeth Warren’s DNA Test Results Actually Mean?” Forbes. October 15, 2018.

Jenny Reardon and Kim TallBear. “Your DNA is Our History”: Genomics, Anthropology, and the Construction of Whiteness as Property.” Current Anthropology 53 (S5) (2012): S233-S245.

Vincent Schilling. “Strike Against Sovereignty? Senator Warren Asserts Native American Ancestry Via DNA.” Indian Country Today. October 15, 2018.

Jamil Smith. “Why Elizabeth Warren’s DNA Fiasco Matters.” Rolling Stone. December 7, 2018.

TallBear v. Moniz, No. 1:2017cv00025 – Document 15 (D.D.C. 2018).

Kim TallBear. “Identity is a Poor Substitute for Relating: Genetic Ancestry, Critical Polyamory, Property, and Relations.” In Brendan Hokowhitu, Linda Tuhiwai-Smith, Chris Andersen, and Steve Larkin. Critical Indigenous Studies Handbook. Routledge, 2021: 467-478.

Mari Uyehara. “What Elizabeth Warren Keeps Getting Wrong About DNA Tests and Native American Heritage.” GQ. December 11, 2018.

WYNC Studios, On the Media with Brooke Gladstone. “By Blood, and Beyond” Interview with Kim TallBear. October 19, 2018.