The essay below is reprinted from Anthropology News, Vol 57, issue 9 (September 2016), with the permission of the American Anthropological Association.

April 2021 Introduction

I wrote the original 2016 essay below to coincide with the opening of the American Anthropological Association’s annual meeting in Minneapolis from November 16-20, 2016. I was asked by Anthropology News to write something that helped explain local context. I decided that I wanted conference-goers who were to be greeted by a “traditional” welcome and Indigenous land acknowledgement, now a common practice in academia, to not rest in a facile recognition of Indigenous peoples, our histories, and cultures in lands now called Minnesota. Rather, I wanted those thousands of anthropologists gathered in Minneapolis to remember the profound Indigenous societies that were the targets of a murderous and white supremacist settler movement that brought the State of Minnesota into being. That history is not only history. White supremacist clearing of the land for white settlement, replacement, and control of the land is an ongoing project.

Illustratively, I wrote the 2016 essay on the heels of the killing of Philando Castile by a cop in the St. Paul suburb of Falcon Heights. St. Paul is one of my hometowns. The Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul are on occupied Dakota homelands. It literally for me hit close to home when a representative of a settler-state police force forged in white supremacist occupation of our home territory, murdered Philando Castile. The cop who killed him was acquitted. The city settled wrongful death lawsuits with Castile’s family.

Last year, on May 25, 2020, another Black man, George Floyd, was violently murdered in Dakota homelands by a Minneapolis cop. Floyd’s horrific death was caught on camera by a teenage girl whose name I learned and remember. I feel so deeply for her and for all of the community members that day who had to watch George Floyd’s life ended by a white cop who nonchalantly with hands in his pockets kneeled on Floyd’s neck for 9.5 minutes. On April 20, 2021, the Peoples (we are many Peoples who can seek good relations; I refuse the colonial designation of “the People”) were delivered the verdict in Derek Chauvin’s trial for George Floyd’s murder. Chauvin was found guilty on three counts: unintentional second-degree murder; third-degree murder; and second-degree manslaughter. Three other officers at the scene of Floyd’s death will be tried beginning in August, 2021. The City of Minneapolis also settled a wrongful death lawsuit with Floyd’s family. Sacrificing a cop here and there to maintain the legitimacy of the settler state will not stop the murder of Black people, nor of Indigenous people and others who challenge white supremacy by their/our ongoing existence and attempts to live free of white domination.

On April 11, 2021, just days before the Chauvin verdict was delivered, another young Black man, 20-year-old Duante Wright, was fatally shot by a cop in the Minneapolis suburb of Brooklyn Center. I watched multiple days of Unicorn Riot’s alternative media livestream as they covered the Peoples protests in Brooklyn Center against ongoing white supremacist police violence in Minnesota, and nationally. My tears were for the tragedy of Duante Wright’s death and in sympathy for the pain his family and community endures. My tears were in regret for the daily assaults and extreme risk that Black people live with in white supremacist-occupied Indigenous lands, and I also cried with thankfulness for the righteous and courageous people in the streets of Brooklyn Center.

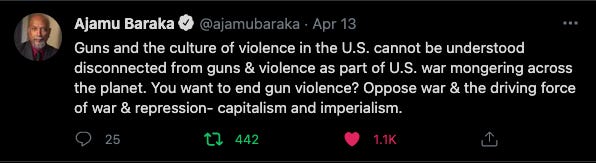

I’ll end this introduction with a screen cap of an Ajamu Baraka tweet from April 13 that links white supremacist colonialism and occupation on this continent to US white supremacist occupation, colonialism, and warmongering abroad. It’s all connected.

(Original Essay)

Before we arrive in Minneapolis for the 2016 AAA Annual Meeting, I share a story that provides formative history, and which may help you understand the storied land upon which you will walk. This account suggests that “making kin” can help forge relations between Peoples in ways that produce mutual obligation instead of settler-colonial violence upon which the US continues to build itself.

The Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul occupy the traditional homelands of the Dakota and Anishinaabe. “The Cities” host a vibrant multi-tribal community. Lakota, Ho-Chunk, Menominee and other Indigenous people have also migrated to the Twin Cities for employment. Known to be a liberal, multi-cultural foodie oasis, the Cities are cut through by the powerful Mississippi River. They were recently dubbed as among the “best of the best” cities in which to live. But livability for whom? Their history is rich and hard, as recently evidenced by the killing of Philando Castile by police in the St. Paul suburb of Falcon Heights.

1862: Settler Greed and Dakota Hunger

In August 1862, a group of young Dakota men were hunting unsuccessfully. Their hunting grounds diminished by white encroachment and suffering long-term hunger, they stopped at a settler’s house to ask for water and food. The settler threatened them with his gun. The young men argued—who among them was brave enough to stand up to the white man? They shot the settler and several others at the home. This was the beginning of war.

The prior decade brought escalating hardships to the Dakota. Looking for title to ever more land, the US repeatedly negotiated treaties with Dakota without having fulfilled existing obligations. The US came to new negotiations with promises that missing funds and goods would be delivered after additional signings. During these negotiations, white traders inserted their ledgers with exaggerated debts to be marked by Dakota who rarely understood what they signed. The Dakota incurred debts with traders for foodstuffs, which they borrowed when the federal government took their hunting grounds yet failed to fully pay treaty provisions. When the US did get around to paying, funds were often eaten up by traders before the hungry Dakota ever saw them.

After killing the settlers, the young men returned to the village of my four-greats grandfather, Chief Little Crow or Taoyateduta. Legend has it that he made a great speech, confirmed by witnesses and later recounted by Little Crow’s son, Wowinape. Multiple sources, including a poem published widely after Little Crow’s death, document Wowinape’s retelling with slight variations between them:

You are like dogs in the Hot Moon when they run mad and snap at their own shadows. We are only little herds of buffaloes left scattered; the great herds that once covered the prairies are no more. The white men are like the locusts when they fly so thick that the whole sky is a snowstorm. You may kill one -- two -- ten, and ten times ten will come to kill you. Count your fingers all day long and white men with guns in their hands will come faster than you can count.

Do you hear the thunder of their big guns? No; it would take you two moons to run down to where they are fighting, and all the way your path would be among white soldiers.

You are fools. You will die like the rabbits when the hungry wolves hunt them in the hard Moon (January). Taoyateduta is not a coward. He will die with you.

The young men called him a coward for his reluctance to go to war against the whites. But Little Crow had tried many tactics during the previous decade—he cut his hair, he incorporated settler fashion into his dress. There are accounts of his sartorial splendor at treaty negotiations, or when he traveled to Washington D.C. to meet with officials. He was curious about those who were different from him. Missionaries were perplexed by Little Crow’s attendance at church where he would listen attentively and thoughtfully. Yet he would not relinquish the ceremonial pipe, nor give up his multiple wives and all of the kinship obligations that came with that. Indeed, Little Crow had grown into an influential leader thanks to his negotiation and political skills developed in large part through kinmaking. At the age of 20 he moved from his father’s village near the Mississippi River where it cuts through what is today St. Paul. He traveled and lived in multiple Dakota communities, spending his young life making alliances by making kin through marriage, birth and adoption. By the time he was 40 he had many relatives throughout Dakota country. There is evidence that this too is how Little Crow approached whites, in both trade and treaty—that Dakota viewed the exchange of pelts and later treaty monies for goods in ways shaped by kinship obligation.

On the other hand, government agents saw market exchanges of goods for money as part of a broader evangelism—the 19th century civilizing project. It included forced conversion to private property, agriculture, Christianity, monogamous marriage and nuclear family. The Dakota had lived and exchanged with French and other fur traders for decades, people with whom they sometimes forged kin groups. But the settler-state had no intention of kinmaking, no desire to learn from the Dakota. The Dakota would either die or adapt to a settler-state partitioning of the world—land, forms of kinship and love, resources and knowledges—into new categories. The settler state has been very poor kin indeed.

On December 26, 1862 the largest mass execution in the history of the US took place in Mankato, Minnesota. 38 Dakota men and boys were hung for participating in the war, their death order signed by Abraham Lincoln. Many other Dakota were imprisoned by US forces, and those who survived prison camps were later relocated to reservations.

21st Century Relations

Some think that the 21st century state has moved beyond coercive tactics that construct non-whites as Others to be either killed or assimilated. Ongoing military and police violence against those others disrupts that fantasy. But so does talk of diversity, inclusion and multiculturalism if we look closely. We see small tolerances for say Indigenous languages, the beating of drums and burning of sage in carefully contained moments. But this represents an idea that Indigenous people should be included into a nation that is assumed to be a done deal, its hegemony forever established. Now, like in 1862, Indigenous people tend to have less interest in incorporation into a (liberal) settler world than in pushing for thriving Indigenous societies.

I propose making kin as an alternative to liberal multiculturalism for righting relations gone bad. Robert Alexander Innes, author of Elder Brother and the Law of the People: Contemporary Kinship and Cowessess First Nation (2013), blurs the lines between Indigenous peoples as dynamic kin groups versus being "nations," with the latter term implying more cultural or even biological/racial stasis. His work opens my mind to a new way of reading people-to-people relations as also potentially making kin. Gabrielle Tateyuskanskan, a Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate citizen, writer and artist, also asks we Dakota to pay more attention to kinship in our analyses of 1862. Some Dakota and European descendants, she reminds us, were already entangled through marriage and family. This could explain Little Crow’s misplaced expectations of kinship from newer settlers. Tateyuskanskan calls for a more complex analysis of 1862 that highlights the political economy of war and conflict. In addition to white racism, how did Twin Cities capitalists benefit from and foment racial strife? The Dakota-US War of 1862 can be read in relation to perpetual US warfare designed to maintain empire and corporate profit.

Calling non-Indigenous people into kin relations as a diplomatic strategy is a new and discomforting idea to me. Today, while Indigenous families regularly make kin with non-Indigenous peoples, we do not tend to foreground this as a form of diplomacy. Since the early 20th century we have focused more on tribal or Indigenous “nation-building” concepts and strategies that include reservation-based, urban and national Indigenous institutions and self-governance structures. But while the language of sovereignty does important defensive work for us it is a partial reflection of Indigenous peoples’ relations with non-Indigenous people, and with each other. The language of kinship may also be a partial and productive tool to help us forge alternatives to the settler-colonial state. Making kin is to make people into familiars in order to relate. This seems fundamentally different from negotiating relations between those who are seen as different—between “sovereigns” or “nations”—especially when one of those nations is a militarized and white supremacist empire.

Looking Forward to November and Beyond

When you arrive in Minneapolis in November some of the first peoples there will welcome you. Their welcome is not simply an example of “local culture.” Recall Little Crow’s kinmaking. Ponder the genocidal actions of the US settler state. Consider how things might have been different had more settlers considered long-established ways of relating and governance traditions already in place. What if settlers hadn’t been dead set on cultural evangelizing through governance, religion and science? Making kin can call non-Indigenous people (including those who don’t fit easily into the “settler” category) to be more accountable to Indigenous peoples and understand their own relations with place. Kinship might inspire change, new ways of organizing and standing together in the face of state violence against both humans and against the earth. Thinking through the lens of kin in our understanding of relations between peoples, and between peoples and place, we might chip away at concepts of race produced in concert with white supremacist nation-building. July 2016 has been a tragic month with the police shootings of multiple Black men. And the racist killings go on. Like my Dakota ancestors, I am heartbroken at the world—both at home and abroad—that this settler state continues to build. I have come to see kinship’s historical veracity and its generous strategic advantage.

May 6, 2021 Edit: Tune into The Red Nation podcast episode, “What is imperialism?” with Nick Estes and Charisse Burden-Stelly for more of this historical Dakota and settler-colonial context as related to contemporary anti-Black killing in Minnesota.

Thanks for this, Kim. I like how you tied together the violence of current events in Minnesota to the violence of the past. So much for Minnesota nice. I'm reminded of Gwen Westerman's telling of the history of this land and people in an episode of Scene On Radio. https://tinyurl.com/yetq7lfs

And thank you for the link to Innes book and your personal reflections on the tensions that can come with how "Making kin is to make people into familiars in order to relate."

I had an awakening in my own piece this week on Interplace as I was re-introduced to Joseph Brant. Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz gives mention to him in her essential read, An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States on page 81 and the history of the Battle of Fallen Timbers. But in researching more about him and his family, it seems he and his Christian White parents were made kin by the Mohawk people.

Much like traditional American history education has avoided the telling the rich and complex multi-cultural story of Little Crow and his relatives, so too have we forgotten the story of Brant - a white Mohawk leader - and his kin. Instead, the area is memorialized by naming Fort Wayne, Indiana after the genocidal murderer, "Mad Anthony" Wayne, in the aftermath of Fallen Timbers.