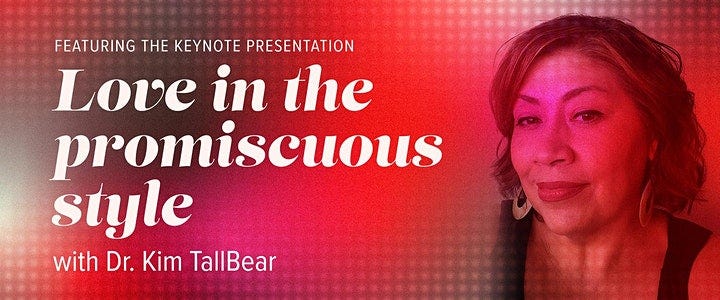

This post is based on a talk I gave for the Sexuality Education Resource Centre (SERC) Manitoba virtual Valentine’s Day Soirée, February 14, 2021. It was a ticketed event and 100% of proceeds went to benefit youth sex education and programming. It was originally posted on this Substack in text only on March 1, 2021. I re-post it today, February 14, 2022 in both text and audio. If you are normally annoyed by Valentine’s Day, this piece that knocks the fetishized (monogamous) couple, romantic, and sexual love off its pedestal—portraying it as simply one among many ways of important relating—may appeal to you.

Some names in these accounts are changed to protect the not-so-innocent. Happy reading and/or listening.

Many people associate the word “promiscuous” negatively with casual and careless sexual relationships. The Oxford English Dictionary defines it as:

PROMISCUOUS, ADJ. AND ADV.

Pronunciation: Brit. /prəˈmɪskjʊəs/ , U.S. /prəˈmɪskjəwəs/

Done or applied with no regard for method, order, etc.; random, indiscriminate, unsystematic.

OED Third Edition, June 2007

Why does this society tell us that promiscuity is always so lacking in purpose? Why do we use this word to shame people for their desires and attractions? Were you taught like I was that ethical sex must be accompanied by romantic love? And that “normal” romantic love is always accompanied by sex? A dominant lesson of our society is that fidelity and commitment go hand-in-hand with scarcity—with the idea that true love is romantic love, that it is rare. And if it is true, then it lasts forever, to the exclusion of other sexual or romantic connections.

I propose that fidelity or faithfulness is not well served by a scarcity mentality, by turning too much toward one individual to meet too many needs and desires. I propose that love is more likely to endure if we allow it to transform; this includes sexual connections. Changes in hearts, minds, and bodies need not mean endings. But if you do happen upon an ending, that does not negate the truth of that love. Sexual connections, loves made and lost are not mis-steps on the way to “the right” one. They are part of the stories of our lives.

Why then lock formative memories behind a door and lose the key when you are fortunate to find new connections, new loves? Your fascinating stories belong to you. And while you don’t owe your accounts to anyone, neither must you silence them as if they never existed. Your stories are yours to share or keep quiet. Of course, be careful with your story’s characters. Remember, you are telling their story too.

In this post, I’ll share three stories and four 100-word poetic vignettes that I sometimes publish on my blog, The Critical Polyamorist, or in edited books or journals. Both the longer stories and the shorter 100s offer personal accounts of relating—stories of love and making kin promiscuously that neither obsess on romance nor diminish romantic and sexual relationships. I focus on multiple connections with many beings—our human beloveds, and our other-than-human companions, especially the relationships that sustain us. That said, not all of the relations I talk about are good relations. But relations that are not necessarily good are also the entangled relations that make and remake us into who we are.

I hope these accounts help guide you toward a generous definition of “promiscuous.” That you might consider the idea, if you haven’t already, that love and care can be enlarged, not compromised or lost, when we embrace a multiplicity of relations.

Fidelitous

I seek multiple tongues. Desires cross time zones. Body stretches like wings over white-light nets taut between peaks and a black, deep sea—life giver. When my first LandLoveBody sleeps on the Twitter feed, intermittent with shots and false dreams, I turn to a European dalliance mouthing into morning headlines of violence in the streets of empire. AsiaPacific spins to the hard day’s end. I am already here. Together we glitter and toast the close of year. Though we remember grief no less. My fidelity is no one-relation bliss. I won’t ask everything: partial sustenance, shared pleasure, stories forged together.

I wrote that 100 in Tokyo around New Year’s 2015. I was there that holiday season as I often am in non-Covid times with two of my dearest ones, the subjects of this first account.

1. Platonic Polyamorous Triad

I may be more dedicated to my triadic (between three) relationship with Jun and Noriko than I have ever been dedicated to a dyadic (between two) romance. Unless a lover turns into family. For example, my daughter’s father is family, although our romance has quieted. I now have several part-time life partners, none of whom I live with: my coparent, Jun and Nori, and perhaps my most recent love of three years—we shall see what the future brings. You’ll meet him in the next account.

While there was a marriage ceremony for me and my coparent, and Nori and Jun are married to each other, there has been no ceremony to seal the triadic compact that I share with those two. I suppose I could do a formal ceremony of adoption. But the medicine man who would perform it would probably: 1) interpret our relationship as an adopted sibling one and confer the terms “brother” and “sister,” and that is not exactly how it works. We really are more like life partners, just very platonically; and 2) the medicine man would do his whole noble medicine man thing throughout the whole day of the ceremony. That level of pomp and circumstance is not really my style. Dakota ceremonies or weddings are nowhere near as expensive and over-consuming as say—a big white wedding. But they are still big to-dos.

Plus, the level of Japanese familial obligation that I am already subject to by having a part-time triad with Jun and Nori is more than enough obligation. I don’t need to add to it a medicine man having a dream about our eternal never-ending bond. It all just feels too much. I seriously doubt I’ll ever want to renegotiate out of my triadic commitments to Jun and Noriko, but you never know—they might get sick of me. At any rate, I think we have more than enough cultural pressure on our relationship.

Ideally, I spend every December and New Year in Tokyo. The plague stopped my pilgrimage across the Pacific this year. Nori and Jun have come to live in my city twice for a year or two when they are able. Two years ago, they came to live in Edmonton for their sabbatical year away from their Tokyo universities. They rented an apartment near the legislature, walking distance from the University of Alberta where they were visiting scholars. They made more friends in Edmonton in one year than I have in five. In the US, they lived in L.A. and New York City. They were both born and raised in Tokyo, a city of over nine million and a metro area of 38 million living within a mere 2,200 square kilometres. For comparison, and this is such a cool statistic, lands now occupied by Canada contain 37.5 million people, virtually the same as the Tokyo metro area, but spread across ten million square kilometres. To Jun, Edmonton is, and I quote, “a village.”

I miss them dearly. We had dinners together a few times a week. I saw them on campus. We’d visit each other’s offices, go for post-work happy hours. We are inseparable when we are in the same city. We are all three professors and critical of US empire, although we are all three shaped profoundly by US history and culture. We met because of our mutual interests in one of the most violent aspects of the US: nuclear weapons development. I know, that’s not sexy, but bear with me. We three were in different cities in the US back in the 1990s, researching environmental impacts of nuclear development on Indigenous lands. One understands how Jun and Noriko, being from Japan, came to an interest in the horrors of US nuclear weapons. I stumbled into it because I got a job with an Indigenous environmental organization. I met Nori first and we became quick friends. She met Jun a few years later.

They got married despite Jun’s formerly womanizing ways. I don’t understand their dynamic exactly. Apparently in Japanese culture you are supposed to insult your spouse in front of others? To brag about them is to brag about yourself. Their dynamic of love and marriage is counter-intuitive to me as a US-indoctrinated person. When I am in Tokyo, I will work long days at their little dining room table while they speed all over the city on the efficient Keio train Line to teach at their respective universities. I barely leave their little house except to take the train two stops to the delectable grocery in the basement of the seven-story Parco department store. I buy things like Skippy peanut butter, apples, cheese, salmon rice balls, French wine, whisky for Jun, and Starbucks coffee. Nori rolls her eyes at my peanut butter.

One year I put Skippy on some super fancy $10 dollar very precious Japanese apple and she ABOUT DIED. They still tell people about the horrific thing I did. Mostly though I eat Nori’s amazing cooking. I turn into a Japanese Salaryman—drinking with Jun while Nori cooks dinner. He will say how awful is his wife’s cooking and she will berate him for things I cannot share with you here. While she is cooking up a gourmet feast in her Uniqlo fuzzy house clothes and her Japanese housewife apron (totally sexy), Jun and I stay the heck out of the kitchen. Until it is his turn to make the fried rice, which is a sight to behold. He’s like a steam engine using the energy of his muscles to shake the wok furiously. I keep my uncivilized, peanut-butter eating self OUT of Noriko’s kitchen. Instead, I drink old lady ume sours and I wait for my dinner of lotus root salad, sauteed greens, perfect rice, and fish. We three laugh long into the night. Mostly we talk about our respective family dramas and the politics of empire. And I gossip to them about my latest polyamorous lover. They ask to see a picture, to hear about the person’s politics, and then they pass judgement. Finally (and please don’t tell the Japanese Salarymen), Jun cleans the kitchen.

Nori and Jun advise me to spend the rest of my life here in Treaty 6 Territory. They also ask that I keep a room for them. Because Tokyo is unbearable in August. As soon as Covid-19 settles down, they plan on summering here next to the North Saskatchewan on the east end of Jasper Avenue, where we shall eat my adequate dinners, or Nori might cook in my kitchen, and I will do the dishes.

2. Marriage Unsettled

Chichibu

Once a decade or so outside my skull in air my own voice hangs. Two winters ago, two hours from Tokyo in a taxi we rolled round switchbacks—a paved mountain road. Village lights and the train station glittered below. From the black night, from beyond cold glass my voice spoke without ado: You may not find the one for you. You found yourself. I grieved. I knew. Later in the house nested like a warm candle in cedar-scented hills the seer completed the vision: He may not find another. When you grow old, you will care for each other.

In addition to my triad with Noriko and Jun, I live daily with two other marriages that have similar dynamics between them: mine with David, and Ted’s with Anna. Ted and I form together the hinge, where our four lives articulate although Anna and David have not met. He lives in the US and never visits Edmonton since our daughter moved back to his city. Before Covid-19, I traveled every other month to see them. David and I have been separated for ten years, but we remain coparents, professional collaborators, easy conversationalists.

We never fight over money or parenting decisions. We are both terrible at paperwork and consider lawyers a waste of money. I am now against the institution of settler-state marriage and would never again marry. So why bother with the dissolution of the state marriage contract? Perhaps David will marry again one day and we will file the papers. Although the seer doesn’t see that happening. Whatever comes to be, we are family in my worldview. We share a child. He has a better relationship with my mother than I do. We may one day share grandchildren.

As for Ted and Anna? What do I feel I can say? I am responsible to caretake their story with a gentle touch. It is part of my story too. Instead of sharing a full script, let me set the societal stage upon which we act out our collective struggles. The colonizer’s stage is not exactly arranged for the kind of imperfect, but trying-to-do-better relations that I share with you here.

Being polyamorous in Edmonton in one’s 50’s is different than being polyamorous in one’s 40’s in Austin, Texas where I began exploring non-monogamy. If you haven’t read Lizzie Derksen’s 2016 Guts Magazine article, entitled “On Being Non-Monogamous in Alberta While the Price of Oil is Going to Hell,” you might want to treat yourself. Derksen, my fellow Edmontonian, suggests that the Alberta oil economy helps produce compulsory monogamy, meaning that monogamy is considered the default, unquestioned societal standard and the obvious moral choice in any good and healthy romantic relationship. She writes:

In my own city…I see oil money being earned in order to establish discrete, traditional, single-family households, I see the loneliness and isolation that result, and I see the excessive consumerism used to combat this loneliness and all the while maintain self-sufficiency…You can’t walk for groceries if you live in Terwilligar, but you can definitely park a couple of SUVs and a boat.

Lizzie Derksen explains how the threat of cheating looms large in a culture where people live isolated in four-car garage houses on the edges of Edmonton or Calgary, counting down the weeks until partners working up north on the rigs come home to Terwilliger or Airdrie. Even close platonic friendships are curtailed due to risk of physical intimacy. Dersken writes from the perspective of a millennial about the challenges of living outside that culture.

Now imagine being in one’s 50s and attempting open non-monogamy here. In Austin, where I moved from, there were polyamorous meetups at patio restaurants and happy hours at trendy live music venues. There was Bedpost Confessions, the sexy storytelling show at an east Austin music club where non-monogamous people of all ages lined up around the block for the once-a-month show. Dressed to the nines. You could tell the ones into kink in their black leather, straps tight across all their sexy places, and their locked collars. They were there to see and be seen.

In Edmonton, we have Earls where the cocktail servers dress like backup singers in Robert Palmer’s 1988 video, “Simply Irresistible,” all of them nearly identical with hair slicked back, in short black dresses, wearing black pointy-toed pumps—an elegant look. For the 80s. I often say that Edmonton is a lot like St. Paul, Minnesota in the 1980s. Before gentrification. Before the North Stars moved to Dallas. It was hockey jerseys, leather jackets, mullets, and steel-toed boots on the working-class streets of St. Paul. I do hear from a stylist at my hair salon that there are swinger parties in Edmonton (or were before Covid) where you can go meet strangers for one-time hookups, or watch others putting their hookups on exhibition for other party-goers. But I am no swinger, I am a vanilla polyamorist who takes longevity of relationships a bit too seriously when I am given the chance.

I also found out that there are married couples in places like St. Albert who have dungeons in the back and F150s in front of the front. Of their McMansions. I found out because they sometimes look for unicorn thirds to enlist in their roleplays. I trust you know what a unicorn is? In polyamorous lingo, it’s that strange, precious, and elusive creature that everyone knows about, but no one has actually seen—typically a younger bisexual woman who will hook up with often heterosexual and monogamish—not totally monogamous—couples. Why would a suburban couple think that I, a 50-something professor, am good unicorn material? Times must be tough for unicorn-hunters in Alberta. A couple from Calgary once told me presumptuously that they were interested in having me accompany them to Victoria, British Columbia for the summer. #1: I didn’t think they were super cute. #2: I have a full-time job.

I am totally down for unsettling settler marriage, but I am not convinced that unicorning is the best strategy. Before Covid-19 hit the polyamory scene, I had my choice of newbies to non-monogamy, I won’t say they were all quite polyamorous. Polyamory is its own elaborate and nuanced system—when done well. It involves lots of sometimes tedious communication. The memes abound about how polyamory is more about talking than sex. And there are even more rules than for monogamy. Because monogamy is wired into us by The Man—in nearly every song, film, and truism we hear. Polyamory takes a lot of re-wiring. And not everyone has the financial or familial or emotional wherewithal to take it on, even if it intrigues them. I have found in Lizzie Derksen’s Alberta that couples in their 50s are well into their third or even fourth decade of marriage. Opening up the creaky, cobweb-sealed doors to their marriages after that long is heavy. Not all who pry it open are open with their couple friends at the community league. Nor with their grown children, who often live with their grandchildren in their own ranch houses on the outskirts of Edmonton. Do you know what your 50-something parents are up to?

At my age, people tend to open marriages to help the settler family structure survive. I think too many of us conflate family broadly with this narrowly-defined structure. Narrow ideas of what makes a good family and what constitutes appropriate sex have been central to colonization. The violence was done first to the colonized, but all of us have had settler norms about sex and family shoved down our throats. And because concepts of property are also central to colonization, salvaging settler marriage is about property and money. Those are chief barriers to unsettling it.

Lizzie Derksen writes about yet another aspect of property in marriage. She explains that one must be “accountable for every moment spent with people other than [a] primary partner.” I have noticed this. I find it odd, the standard of constant togetherness. Costco in Sherwood Park is filled with middle-aged couples who look annoyed with one another. I wonder why they both need to be there. They should trade off their Costco runs every other Saturday. And the other one meet with their lover for a couple of hours. But instead, there is this counting of moments spent elsewhere, even despite years of coolness that have quieted playful, teasing banter, foreclosed gentle touch or passionate probing. All this accounting: “Where were you? Why are you late? I did all of this. And you haven’t done that.” This is settler-colonial coupledom: treating partners like land, like property to be invested in and developed for a sufficient return, a nest egg for a rainy day that needs to be subjected to strict accounting procedures.

Yet because we’ve internalized and built lives around this property institution, we tend to think that salvaging marriage is necessary to salvage our families. I do not advise, of course, that you get married, but if you already are long married, I get the arguments for not leaving. Ending marriage contracts can risk our housing, our ability to feed ourselves and our children, it can tear our hearts and families apart. This is why I encourage us to resist equating an intact marriage and the couple with an intact family. We may end or not our state contracts, but regardless, can we renegotiate those partnership agreements according to more flexible rules that might help us better sustain our hearts and bodies while making our relations with one another even more mutually sustaining? I know it may seem impossible. But an idea planted now may one day find the nourishment to flower.

Let me share a quick story within a story about another mutual relationship that encountered a hiatus. It was a relationship just as profound, and sustaining, and shaping of personhood as any human marriage.

I taught an intensive course in Tokyo. One of my students wrote about the material and energetic intimacy between humans and trains. He wrote not only about the physical, but psychic devastation for the people of Sendai when the trains stopped for days after the 40-meter-high tsunami hit the east coast of Japan, March 11, 2011. The student wrote about the centrality of trains to daily life. Their passage every couple of minutes like a heartbeat until the heart stops. The trains are a rhythm of life for the people. The absence of train vitality added to the apocalyptic experience of one of the most powerful earthquakes ever recorded and the subsequent deadly tsunami. That also left spirits wandering streets, asking taxi drivers to take them to homes flattened under the hurling of the sea. When a driver looked in the rear view to say “but that neighbourhood is gone,” so was the passenger.

Like when the trains stopped running in Sendai, how do you stop the rolling engine of a marriage of 20 or 40 years? What is your life without its heartbeat? Even if it’s a weak or erratic heartbeat? So many marriages are insufficient in the kind of intimacy that some of us crave desperately, but others don’t much need. Some people dream constantly in waking and sleeping moments of touch and warm, wet intimacies, of the smell and feel of a lover’s body skin to skin. Other people feel absolutely smothered by the thought of a lover’s limbs or mouth wrapped around them, thrusting into them. They prefer soft fabric, the weight of a quilt, a good book, a back rub until sleep. True love can involve different kinds of intercourse, maybe none of it physical.

Early on in my polyamory experience, I had relationships with a couple of vanilla men whose wives needed BDSM. “Vanilla” is what kinksters call the rest of us. The men I dated agreed to open their marriages so the women could fulfill needs their husbands had no desire to meet. It was fascinating to watch them work with each other’s differences. I learned a lot by watching them give each other space to develop other intimacies.

I remember being at Henry and Autumn’s one night—in their home out on the Texas plains. Henry and I had just had dinner and were cuddling on the couch. Autumn called. She’d been planning to spend the night with a lover. But she started to feel ill and wanted to come home and sleep in her own house. Henry asked if I was okay with it. “Yes, it’s her house,” I replied. When she arrived home, she greeted us both with a hug. Then she went to the guest room, leaving Henry and I to our romantic evening and to the bed in their master suite. I thought “Okaaaaay.” It made an impression. Autumn with her warmth and graciousness became a role model for me.

Henry had zero appetite for the domination that Autumn sometimes craved. Sometimes our modes of connecting and our needs are simply unbridgeable. Should one partner then suffer silently? Other unbridgeable needs are also genuinely important. For example, I know that dutiful sex without desire can be soul-crushing. So can compulsory celibacy. An asexual polyamorist once blew my mind. They told me that while they never really crave sex, they will sometimes have it with one of their partners who is sexual. Because they love that partner and they want to do for them. Not everyone who doesn’t explicitly crave sex can do that. I do learn much about good relating though from asexual polyamorists. Marriages sometimes open to end one kind of suffering and to prevent another. Many polyamorists will tell you that is not a good place from which to open a marriage. Opening up a troubled marriage won’t save it. Probably true. But I do not advocate marriage salvage as much as I advocate making better relations. If open doesn’t work, then maybe transitioning out of marriage will make you better kin?

Since arriving in Alberta 5 ½ years ago, I have encountered many unsettled marriages, including Ted’s and Anna’s. I recognize their relationship patterns that I mostly am not speaking of here. By accompanying them on a bit of their journey, I have learned about my own unsettled marriage. For 13 years I squeezed myself into the box of a marriage that had similar dynamics. Trying to fit inside that relationship structure was the hardest thing I have done. And leaving was the deepest hurt in my life, and the greatest pain I have caused another person. This is why I try not to offer advice in Ted’s and Anna’s marriage matters. After a decade, I still go back and forth wondering if I made the best decision for my own marriage.

Speaking for myself, all I knew was what pop country singer, Sunny Sweeney, sang:

You don’t go until you’re praying to break even,

Until staying is worse than leaving

God knows we tried everything that we could do

You can keep your pride and blame me if you need to

It turns out we didn’t try everything. I did not know that I could or should ask for a different kind of relating, a differently shaped household. I found myself miserable in a monogamous marriage, presenting as a respectable nuclear family in a single-family home in a densely populated, overpriced city. I then made the intellectual leap to thinking perhaps he’s the wrong “one.” You know, “the ONE,” like your Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ? I thought that. Even though I was raised happily by grandmothers in sometimes “overcrowded” extended family conditions in the middle of a sparsely populated prairie. We were not middle-class and we had few married couples around to contaminate the matriarchal bliss.

I was also a little confused about which sets of relations were contributing most to my misery. Was it mostly the nuclear family standard? Or was my misery also sparked by being a displaced prairie person? I felt hemmed in between the mountains and sea of central coast California where we lived. Those mountains’ energy pushed, pulled, jostled me. The sea is an expanse of other Peoples’ water spirits. Could my ancestors find me there when I die? I shuddered to think of my spirit being stranded on the precipice of a deep, dark sea. With each year that passed in California, I felt more and more alienated. Yet I also felt smothered not only by mountains and hills all around but by millions of people. I longed for the tumultuous skies of the vast, empty prairie.

It took a few years for me to understand that two things were intolerable. First, my alienation from the prairies of my heart. And second, it was not my co-parent, my friend, my co-thinker who is an ill fit. He is just not my only fit. But the structure of our marriage helped alienate me from my grandmother-centered, woman-centered universe. Settler marriage with its compulsory monogamy, nuclear family and property obsessions, its couple-centricity, its respectability roleplay—is such a drag. Even if it takes a more “progressive,” non-oil economy form, colonial marriage continues to break my heart year after year as I struggle to live differently in a world conditioned by it, and as I watch people I love struggle too.

I wish I understood ten years ago, what I understand now. I might have made gentler, wiser choices. I wish I had known to ask my co-parent, my humble and kind co-thinker, to join me in exploring non-monogamy. Perhaps I could have asked him to plan with me for separate apartments, down the street or down the hall from one another if we could afford it. He was tired of my nagging about cleaning anyway. He might have tried non-monogamy. He’s sex-positive and he’s a feminist. Moving to the prairies would have been harder sell. But I did not know that I could ask for such things—that it was legitimate to want them. The consequences of unsettling marriage and the couple-headed family are painful and filled with loss, as was the colonial imposition of these cultural practices and laws that uphold them. My wish for all of us is that we can get off this damn stage, and write new scripts, new definitions.

PROMISCUOUS, ADJ. AND ADV. (NEW DEFINITION)

Pronunciation: Brit. /prəˈmɪskjʊəs/ , U.S. /prəˈmɪskjəwəs/

Plurality. Not excess or randomness, but openness to multiple connections, sometimes partial. But when combined, cultivated, and nurtured may constitute sufficiency or abundance.

3. Love in Bones and Flesh

I open this final story with another 100 inspired in part by the voice of a colleague, professor and artist, Natalie Loveless. The bones of this 100 came to me at her book launch in October of 2019 at Latitude 53, a gallery in downtown Edmonton. It was dark and quiet outside, but lively and well-lit inside. We crowded all together in that before-Covid time. I sat among friends and art and sipped wine. As Natalie spoke in her elegant way, I scribbled notes on a slip of paper. Thank you for being my muse, Natalie. And thank you, Ted, my love of nearly three years, for the inspiration of fine body to compare with a fine wine.

Cacao. Sea. Sweetgrass. Earth

Her 99% cacao voice melts over us, pressed together in well-hung space. At the art gallery book launch, perched on chairs too spare for ample bottoms, I trace the glass’s edge with a thumb’s soft inside. Not unlike how I graze your perineum. Lids close, lips open, tongue tip probes the rim. Italian tide rolls in, stone and gold. Then pulls back—a placid goblet sea. A drop on my chin. Aftertaste of cut prairie grass in that other teasing in-between, the border zone of nose and palate. I sip liquid earth in wine. I sip the sea from you.

There was a time when I couldn’t wait to leave the lands and rivers that constitute the flesh and blood of my heart. At fourteen years old, I ran gravel roads in the summer evenings, a couple hours after my grandmother’s tasty, simple suppers. I ran out the screen door of our house, one-quarter mile down the dirt driveway to the gravel road. I’d turn right, run another one-quarter mile to the two-lane highway and sprint across Rural Route 2 although I didn’t need to. A dozen cars an hour would pass. On the other side of the road was the slow brown river where my grandmother fished on summer days, the river next to the pow-wow grounds. I remember the smell of sweet grass and a rainstorm coming. I’d turn toward home quickly, running to beat a high purple plateau of clouds. Clearly, the majestic beauty registered deep in my bones, but at the time I didn’t think anything of it. I thought all skies were like that. Later in the black starry night, I would lie next to my open window with cows mooing on the white farmer’s hill behind our house. I would put myself to sleep with dreams of taking that highway out from our country.

The title of this vignette, “Love in Bones and Flesh” is inspired by a lyric written by singer-songwriter, Lori McKenna. Her music is saturated with settler sex and marriage, but that’s true of most of the country music that I love and primarily listen to. My co-parent noticed before I knew it about myself that I love contradictions, including contradictory people. I also love guitars and fiddles. And banjos. And I love songs with stories in them, songs about place, and the troubled, wandering humans who are always loving and leaving place.

Or in the case of Lori McKenna, the humans trying to make things work. She’s from Stoughton, Massachusetts. She sells songs to famous singers in Nashville, but I prefer when she sings them. She’s less glitzy, more authentic. She and I are the same age. And I love her music, her story-songs about place and kin that are both familiar to me and that contradict my experiences of country and family. Some of her songs are noticeably Catholic to me as a Dakota raised between the ceremony of a staid little Presbyterian church on the prairie, and Dakota ceremonies. Sometimes we’d go to ceremony with Ojibway people, especially at their maple sugar camps in Ontario. My mom would drag us four kids north in spring. We’d spend long sunny days in the woods. The campfire smell was heaven. The nights were cold, but the sweat lodge was hot. We’d sit cross-legged in the dark lodge around glowing red rocks. One time, I felt I was looking back to the beginning of the universe as I stared at those rocks and their life-giving fire within.

The rest of the year, I lived with my grandmother at the edge of the small town the white people plowed and leveled, where they laid train tracks into earth. Lori McKenna’s songs are about the way whites live in provincial towns. They are the kinds of stories we are all supposed to aspire to. Songs about marrying a high school sweetheart, having children, selling your guitar when the baby comes—nuclear family story-songs laced with quiet, encouraging judgement. “Don’t steal, don’t cheat, and don’t lie.” Learn from one-night stands. They’re not real love. Relations without an engagement ring are men playing games, and you are worth more than that.

These corseted narratives, American myths in song, offer reassuring scripts. I see in my head the houses and roads in Lori McKenna’s songs. I recognize the tenderness and comfort she sings of, sleeping with her child—keeping them close and safe—instead of sleeping with her husband. I recognize the worry about half the bills getting paid. She could be singing about Stoughton, Mass. or Saskatchewan or South Dakota. I keep listening to her deft fingers on perfect strings as I watch the snow outside my window north and west from those maple sugar camps, here in Alberta on the prairie’s edge.

McKenna sings one song I listen to on repeat, “The Lot Behind St. Mary’s.” I tear up every time at a line near the end.

But now we're old enough to know…that God's love is almighty, but our love is just bones and flesh.

It’s a sad line to me and, I think, misguided. It is heaven vs. earth, spirit vs. body, holy vs. profane. It is a harsh divide that colonial Christianity brings to this land. It is not only Dakota or Ojibway or Cree who suffer for this. We all suffer from the denigration of bones and flesh. Yet our bones and our flesh emerge from the bodies of ancestors. Our ancestors emerged from water and earth. Before that, ancestors emerged from the stars. Stars continue to nourish our bodies and this planet. Whether God is involved or not, our bodies go back to the ancestral planet, like salmon bodies that die to spawn then nourish their descendants. It seems to me that bones and flesh born of the mystery and energy of the universe, give us the most profound connections we have.

On that note, I leave you with a final 100, written as instructions to one of the loves of my life, my daughter, Carmen.

River Quantum (instructions for Babygirl)

1/4 my ashes to be spread across the North Saskatchewan. When ice flows and is lit by sun at a bend in central Edmonton. 1/4 to be blown across the heavy Mississippi. Back to ancestors at Minneapolis, St. Paul. 3/8ths shall be offered up to the Big Sioux. Next to the old pow-wow grounds, make sure! That river is akin to my grandmother who fished its waters on close-to-home days when she did not venture to the Missouri. 1/8th, the remainders of me, shall be emigrated to the Corrib, my tumultuous river love near Galway’s cathedral where I cursed Columbus.

Share this post