Everything within a settler colonial society strains to destroy or assimilate the Native in order to disappear them from the land - this is how a society can have multiple simultaneous and conflicting messages about Indigenous peoples, such as all Indians are dead, located in faraway reservations, that contemporary Indigenous people are less indigenous than prior generations, and that all Americans are a “little bit Indian.” These desires to erase - to let time do its thing and wait for the older form of living to die out, or to even help speed things along (euthanize) because the death of pre-modern ways of life is thought to be inevitable - these are all desires for another kind of resolve to the colonial situation, resolved through the absolute and total destruction or assimilation of original inhabitants.

In October 2019, I gave a keynote at the Duke University annual Feminist Theory Workshop. I noticed that there was no land acknowledgement given to open the event, a by-then standard protocol across Canadian universities and many other institutions. I am not judgemental about the lack of land acknowledgements at some institutions, for the simple reason that I think they cannot be written in historically and politically robust language without lengthy consultation with Indigenous communities, and not all institutions have sufficiently extensive or good relations with Indigenous communities. It may be better not to do a land acknowledgment than to do it poorly and before one has built the necessary relationships to undertake the task. That said, there is no non-embarrassing excuse for the erasure of Indigenous-to-the-Americas history/presence in any event held on these lands. But a land acknowledgment is only one narrow strategy for making Indigenous life visible.

Nonetheless, I am sufficiently indoctrinated into everyday and widespread Canadian academic protocols after 6.5 years living here, and I still felt a little uncomfortable without any form of land acknowledgement or Indigenous welcome on stolen land. I quickly found what seemed like a reliable online map of Indigenous peoples whose traditional territory is occupied by the area of North Carolina where we gathered. My feeling at the Duke symposium was that naming those Peoples was an important moment. Such statements may be most powerful when they are surprising.

In an interview with Rosanna Deerchild on CBC Unreserved in January 2019, Hayden King, Anishinaabe from the Beausoleil First Nation in Ontario, Ryerson University professor, and Yellowhead Institute director in Toronto, provided a short history of land acknowledgements in Canada. He noted that the circumstances in which land acknowledgements are given matters:

There is a danger of the acknowledgement just becoming the excuse, through which these institutions provide themselves permission to be on that territory…[If] maybe the acknowledgement is just evolving for the first time, then it does have the power to compel a conversation…I think in settings where it’s an unfamiliar practice or a new practice, I think beginning with that acknowledgement…that’s a good thing.

Of course, the surprise does not last long, and we are left in many cases with pro forma statements or acknowledgements that do very little to change anything. King notes that “the territorial acknowledgement is by and large for non-Native people…It effectively excuses them and offers them an alibi for doing the hard work of learning…about the treaties of the territory and learning about those nations that should have jurisdiction.”

This is effectively the perspective expressed in an opinion piece published on October 7, 2021 in The Conversation by three anthropologists, Elisa Sobo from San Diego State, Michael Lambert (Eastern Band Cherokee) from the University of North Carolina (UNC)-Chapel Hill, and Valerie Lambert (Choctaw Nation) also from UNC. They lament that land acknowledgments commonly given “not only at events but in email signatures, videos, syllabuses, and so on”, can communicate erroneous historical ideas and do not demonstrably “lead to measurable, concrete change.” Rather, the authors assert, such acknowledgements place Indigenous peoples in the past, do not acknowledge the depth of colonial violence used in attempts to conquer Indigenous lands and eliminate Indigenous peoples, nor do they call for land back.

Instead, the implication of most land acknowledgements is, “What was once yours is ours now.” The authors call for acknowledgements that also advocate land back and “a sincere commitment to respecting and enhancing Indigenous sovereignty.”

Even the right-wing media outlet, The Epoch Times published an article on November 8, 2021, “Indigenous Land Acknowledgements Questioned as ‘Land Back’ Movement Grows.” Some non-Indigenous Canadians are apparently a little perturbed about all this #Landback talk. The Epoch Times article cited a CBC news story and leaked memo from mid-October, when “New Brunswick Attorney General Ted Flemming advised government staff to stop issuing land or title acknowledgements in ‘meetings and events, in documents, and in email signatures.’” The Epoch Times paints land back as unrealistic, but their coverage demonstrates the growing visibility of land acknowledgements and Indigenous movements in the US and Canada that call for return of land.

Performing Indigenous: Your Identity is Ours Now

Such worries are contrary to land acknowledgement critiques expressed in The Conversation piece by Sobo, Lambert, and Lambert, pro land back critics of pro forma land acknowledgements. They worry that land acknowledgements reinforce settler state claims to the land: “It’s ours now.” They also worry about who is sometimes called to perform them. They explain that “such rites often feature voices of people who… ‘play at being Indian—that is, those who have no legitimate claim to an Indigenous identity or sovereign nation status but represent themselves as such.”

I assume the authors, in expressing this worry, are referring to individuals thought to be Indigenous community members, who are contracted by universities to give blessings and “traditional” welcomes. My Faculty of Native Studies at the University of Alberta has relations with local elders who we often call on to give such welcomes and blessings. But our faculty is also populated by Indigenous people from this region who have reliable networks that we can draw from. The same is not true of all universities.

As evidence for their worries, the authors cite US census data based on “American Indian and Alaska Native” self-identification, which they compare to federal data on tribal nation citizens. The authors assert that “pretendians” may outnumber actual Indigenous people in the US by 4 to 1. Of course, most of us with tribal nation status have relatives without citizenship, so numbers of people illegitimately claiming to be Native are difficult to get at. Still, the 4 to 1 disparity is high and troubling.

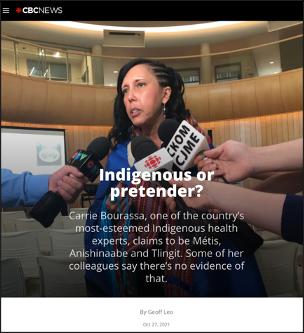

In Canada, we recently suffered the outing of the Scientific Director of the Institute for Indigenous Peoples’ Health at the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR). Dr. Carrie Bourassa of the University of Saskatchewan claimed to be “Anishinaabe Métis” and to have Tlingit ancestry. On October 27, 2021, CBC broke a story that according to their research, there was no truth at all to Bourassa’s claims to be biologically descended from any of the aforementioned Peoples. You can watch a video of the story here.

After the story broke, Dr. Bourassa began claiming instead that she had been ceremonially adopted by a Métis elder. During the last week of October and the first couple of weeks in November after the story broke, the media was replete with images and a TEDx video of Bourassa adorned in traditional garb and holding a feather. Holding back tears, she introduces herself by a name she says she received in ceremony, “Morning Star Bear.” Bourassa is one of several high-profile cases of alleged Indigenous identity fraud broken by the CBC in the past few years. Each case has involved heavily curated performances as Indigenous by those accused of totally fabricating or greatly exaggerating their claims to Indigenous affiliation.

On November 1, two unprecedented things happened. The CIHR president announced that he and Bourassa agreed that she would “step away from all of her duties as scientific director of the Institute” and would “be on indefinite leave without pay effective immediately.” After initially defending Bourassa in an October 28th statement, the University of Saskatchewan did an about-face on November 1 and placed Bourassa on leave as well. Then on November 17, CIHR announced they are cutting ties with her. Finally, on November 18, the University of Saskatchewan announced that they appointed an independent investigator—a high profile Métis attorney—to examine Bourassa’s identity claims.

I can think of no other example in which an alleged Indigenous identity fraud has encountered such swift and definitive professional sanctions.

I grew up in a world where I was familiar with Indian play from a young age. I remain both unsurprised by how widespread it is and yet continually surprised by how brazen and extensive are the made-up stories. Often, such claims appear impervious to questions from the actual Indigenous people implicated, and the institutions that represent them. Dubious claims hang around, year after year, with perhaps only a few brave voices persistently articulating their doubts. Sometimes, however, stories fall apart. Rarely are there significant personal or professional consequences.

In January 2019, I wrote a High Country News article about Elizabeth Warren and her claims to Cherokee identity. In that article I described a t-shirt I purchased at a pow-wow in the early 1990s when I was in my early 20s. It read “No! My great-grandmother was not a Cherokee princess!” That declaration referred to the common practice of non-Natives who have no lived Cherokee experience and no tribal nation citizenship, but who claim affiliation based on a family myth of a Cherokee great-grandmother, often with stereotypical reference to an ancestor who had “high cheek bones” or “olive skin” or long, straight, dark hair. The myth is so common that it produced the t-shirt I purchased thirty years ago.

Not only Cherokee people are burdened with this myth. There are few places I can go in the US without being subjected to this stereotypical and appropriative settler-state narrative. I also regularly receive long emails from people telling me their long-ago Cherokee or other Native ancestor family stories, and who ask for DNA testing advice. In my research and writing, I directly challenge the conflation of narrow and distant ancestry alone—actual or alleged—with substantive claims to Indigenous belonging. It thus surprises me when people who say they’ve read my work on the topic, nonetheless write me with their genetic ancestry test questions. Did they grasp a basic understanding of my words?

Not standing as, but standing with

Part of countering the stereotypical expectations of settler-colonial society is also my refusal to strike an expected pose in teaching or in public performances of scholarship and media commentary. I am mindful to avoid, especially before non-Native audiences, performances that align with their common views of Indigenous people erected around binary juxtapositions of tradition versus modernity, past versus present. I am acutely allergic to “noble savage” representations produced of those binaries, wherein the traditional Indian is supposed to be stoic and wise, both close to nature and yet other-worldly and untouched by the material concerns of the world.

We discussed in a Media Indigena “rapid round” episode on November 8, 2021 “how some people ‘Indian Up’ their appearance for non-Indigenous audiences.” We laid out the pros and cons of (performatively) wearing regalia, for example, at a United Nations meeting or at conferences and other venues where Indigenous people might be a small minority and/or susceptible to being viewed as curious relics of the past. Is one performing for a non-Indigenous gaze, or insisting on one’s community norms and pushing back against Indigenous erasure? There are, of course, ways of communicating and signaling group insiderness that do not also constitute performance for the non-Cree, non-Dakota, or otherwise non-Native gaze—strategies that are satisfyingly inaccessible to a non-Indigenous audience.

Not that one cannot do both, but I tend to eschew more obvious representations of my individual person as Dakota, “Native,” or “Indigenous,” and instead try to ground my thinking, research, and voice in a collectivist approach I explained in a 2014 Journal of Research Practice article, “Standing With and Speaking as Faith: A Feminist-Indigenous Approach to Inquiry.” I had for much longer intuited the ideas described in the article, but I was able to voice or give language to them after encountering cultural studies scholar Neferti Tadiar’s explanation of the Tagalog term, “sampalataya,” which she translates as “act of faith.”[1] Tadiar uses sampalataya to describe the idea of how to speak from within rather than on behalf of a group. I describe in my article my application of her idea to my own research ethic:

Rather, one speaks as an individual “in concert with,” not silenced by one’s inability to fully represent one’s people. I read this to be a sort of co-constitution of one’s own claims and the claims and acts of the people(s) who one speaks in concert with. Sampalataya involves speaking as faith—as furthering the claims of a people while refusing to be excised from that people by some imperialistic, naïve notion of perfect representation (4).

This approach is central to my anti-hierarchical and co-constitutive (with community, but not necessarily “traditional”) knowledge production practice. But I am left to ponder now what it means for my performance for various audiences. I perform for audiences whether verbally or in writing, as an authority, with an authoritative voice. And I perform my voice and persona as a Dakota woman. In this historical moment, I am also interpreted as an “Indigenous” voice. [I bracket the contestability of the term “Indigenous” for now.] When I use the term “performance,” I do not imply something untruthful or put on, but my meaning is basic: “to carry out a task.” In my public performances of research and other thought, I stand with; my claims are co-constituted with other Dakota and perhaps broader Indigenous claims because those are the standpoints from which my specific curiosities and questions have arisen in the course of my living. I speak in order to further collective claims. In so doing, I do not attempt some “naïve notion of perfect representation.” I do not need to. I should not do such a thing. Such moves would feel paradoxically inauthentic and suggest a negative connotation of performance, something “put on,” and, crucially, to treat one’s people as artifact. I am, we are, “already caught up in the claims that others act out,” and we can therefore speak “in concert with.”[2]

I could certainly dig into performance studies for more nuanced language around “performance,” but time is short. I do welcome citational suggestions.

I circle back now to Indigenous identity fraud. Sometimes, in their attempts to achieve that “naïve notion of perfect representation,” and to do so particularly in the absence of lives co-constituted with the collective lives of a People, writers and artists, actual performers, and performers of research, blessings, and land acknowledgements put on accoutrements, both material and affectual. This is to Play Indigenous, or as Philip J. Deloria describes it in his 1998 book, “Playing Indian.” To be clear, performing Indigenous can come to stand in for standing with. Exaggerated and obvious performances of individual ancestral claims and affiliations should not substitute for acting on, with, and through lived relations with a community or People. In the academy, especially—or maybe it’s just where I see it most because it’s where I spend the most time—such performances are too common.

Performing Indigenous hinders land back

I want to make a forceful case against attention policing. Given my area of research, I’ve often heard that critiquing identity fraud, including the fetishization of long-ago genetic ancestry in support of such claims, is a distraction from more pressing problems that Indigenous peoples confront: environmental assault, health disparities, poverty, intergenerational trauma, high rates of missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls, and two-spirit people, police profiling, high rates of incarceration, and the list goes on. It both surprises me and does not that few people seem to understand that societally-entrenched Indian play, its resulting theft of economic resources, and widespread acceptance of the practice are mutually-constituted with more obvious forms of settler-state theft of everything Indigenous: land; water; natural and biological “resources,” including blood, bones, and DNA; the theft of children and other vulnerable relations; and the extinguishment of Indigenous social practices and governance authorities. This expansive list of settler-colonial approaches to extinguishing and appropriating all things Indigenous can be seen as a comprehensive, centuries-long, and ongoing approach to Indigenous elimination whether settler-state citizen perpetrators know it, or not.

State multiculturalism, including territorial acknowledgements not linked to Indigenous land and life return might seem democratic and inclusive on its face, but it is also an assertion of ownership over First Peoples and their territories. It is a denial of Indigenous governance authorities. The final stage of denial is an assertion that Indigenous Peoples and rights are not actually separate from the settler state. Self-Indigenization, “We are you,” does not require the assent of Indigenous collectives themselves, just like Indigenous peoples need not give assent to settler-state appropriation of land and resources.

Land acknowledgments and self-Indigenization as property grabs

Let’s return to the Sobo, Lambert, and Lambert critique in The Conversation. They assert that most land acknowledgements imply that “What was once yours is ours now.” This includes not only land, but moral and governance authority. Indigenous peoples get lodged in the past as an ever-vanishing race:

Take, for instance, the evocation in many acknowledgments of a time when Indigenous peoples acted as “stewards,” or “custodians” of the land now occupied. This and related references – for example, to “ancestral homelands” – relegate Indigenous peoples to a mythic past and fails to acknowledge that they owned the land. Even if unintentionally, such assertions tacitly affirm the putative right of non-Indigenous people to now claim title.

Pro forma and past-tense land acknowledgements, although they have a veneer of inclusion and respectful recognition, are not incompatible with settler-colonial denial. This is especially true if acknowledgements are not followed by commitments to social change—to the return of Indigenous land and life—meaning Indigenous cultural and governance authorities, institutional capacities, relational structures, and sustenance that are co-constituted with land and water.

Instead, what is “ours now”—that is, what is judged to belong now to the settler-colonial state and its institutions—is not only the land. In the past several years, media outlets and Indigenous organizations in the US and Canada have called on me to comment on “identity” fraud cases. I have addressed the problem assertively, and have faced tremendous resistance from both non-Indigenous and some Indigenous people too. The experience has led me to a realization: pervasive assumptions in the US and Canada that these two states have moral and legal rights to claim the land go hand-in-hand with a widespread belief in the right to claim Indigenous “identity” and with it, professional titles, opportunities, and resources. I wrote about this strong link between land theft and identity theft in a June 14 Substack post, “We are not your dead ancestors”:

It has become clear to me that confronting this form of theft is as formidable a challenge as confronting the core theft of settler colonialism: false and illegal claims by the US and Canada to Indigenous lands and waters. The nation state’s debt for genocide committed against Indigenous peoples, and the almost total appropriation of Indigenous land and resources will never be repaid. Genocide cannot be undone. Even #LandBack, an at once inspiring and pragmatic move, cannot restore our ancestors who were stolen, starved, who died of broken hearts, massacres and sickness. Even #LandBack is still unfathomable to most non-Indigenous citizens. It is unfathomable to some Indigenous people too. Imagine how many Canadian and US citizens would balk at the idea that Canada and the US illegally occupy much of their territories, that they lack moral authority [to govern them]? That is essentially the same conceptual mountain we face in saying that well-paid and well-known people like politician Elizabeth Warren and academic Andrea Smith in the US, novelist Joseph Boyden and film director Michelle Latimer in Canada have no moral or legal rights to occupy the identities they claim and the attendant resource and psychic benefits of reverse passing.

Identity or relations?

I have taken to putting the word “Identity” in scare quotes. It is a word to which I am developing an acute allergy. I am forced to use the word because it is what settler-state culture thinks we are talking about—or maybe “identity” is its clever distraction? When non-Indigenous people claim Indigeneity, and in the process grab resources, professional authority and political power, this move commonly gets referred to as “identity” fraud or false “identity” claims. But I am not talking about identity at all. And I would like you too to stop talking about it so much. Let me explain and perhaps convince you to adjust your ideas and language when possible.

The popular concept of “identity” as it gets used in relation to Indigeneity or in relation to First Peoples, does not necessitate active relations with those collectives, nor serious engagement with their social mores and institutional authorities. “Identity” can refer to molecular patterns—biological and not necessarily social relationships—one’s “ancestry.” Such biological relationships and connections can be sparked by and/or spark lived social relations; on the other hand, they might not. “Identity,” even when viewed as a cultural rather than biological property, easily exists as an individualistic claim, as something held within one’s own body as one’s body’s property. Identity just as easily distracts us from Indigenous land and life as much or more than it supports it. “Identity” is a poor substitute for relations, including not only our familial, “tribal”, and other human kin, but it is also a poor substitute for our relations with nonhuman relatives and the places with whom First Peoples are co-constituted.

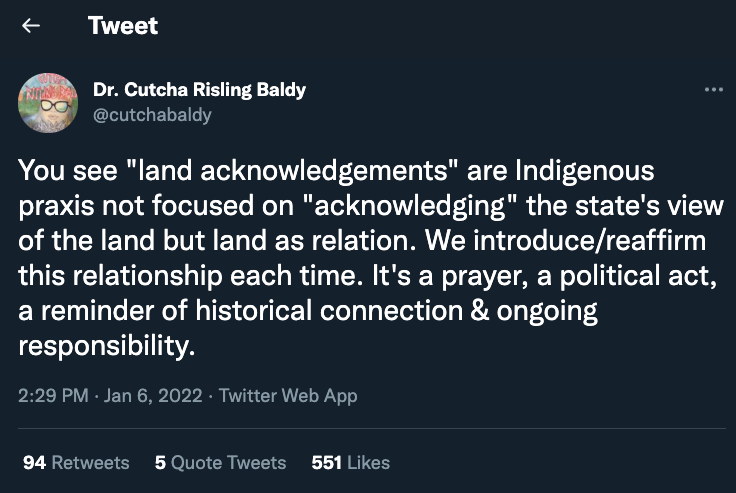

Consider this January 6, 2022 tweet by Dr. Cutcha Risling Baldy who is Hupa, Yurok, and Karuk, and an Associate Professor of Native American Studies at Humboldt State University in California.

The professor illustrates how land acknowledgements given by Indigenous people in longstanding relation with place are fundamentally different from land acknowledgements issued by non-Indigenous speakers and institutions. The latter tend to take for granted the legal and moral legitimacy of settler state occupation and authorities while ascribing a past-tense nature to Indigenous authorities. Cutcha Risling Baldy’s tweet insists on ongoing Indigenous governance and relational responsibilities. It is consistent with the idea that the settler’s individualizing, human-centric (co-constituted with white supremacy), and property-based redefinition of relations—is definitionally and pragmatically opposed in Indigenous pushback to appropriation in its many forms: theft of land and Indigenous children; the forceable replacement of Indigenous governance, ceremonies, and family forms with settler laws, religion, and family, including our most basic rights to determine who belongs to us.

Yesterday morning (of January 26, 2022), yet another Indigenous woman scholar, Celeste Pedri-Spade, an Anishinabekwe (Ojibwe) from northwestern Ontario and a band member of Lac Des Milles Lacs First Nation, published an article—also in The Conversation—addressing so-called re-indigenization in the academy that pushes back on the tiresome and distracting “identity crisis” and “identity politics” narratives. I give her the final word here. In the op-ed entitled “We are facing a settler colonial crisis, not an Indigenous identity crisis,” Pedri-Spade sums it all up:

“Mining” the archive for biological trace(s) of “nativeness” follows the same settler colonial, possessive and extractivist logic of mining Indigenous lands.

Both Indigenous lands and identities are positioned as resources that people are entitled to claim and own.

*This essay was given in an earlier iteration as an invited lecture to the North Orange Community College District for its Pluralism, Inclusion, & Equity Series, Anaheim, CA, USA, November 19, 2021.

[1] Neferti X.M. Tadiar, “The Noranian Imaginary,” In R.B. Tolentino (ed.) Geopolitics of the Visible: Essays on Philippine Film Cultures (pp 61-76). Manila, Philippines: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

[2] Ibid. Tadiar, 73.

Beyond Indigenous Performance to Life and Land Back